July to September 2014: Mexico and Central America

ForumReading Globally

Melde dich bei LibraryThing an, um Nachrichten zu schreiben.

1StevenTX

Mexico and Central America

Welcome to Reading Globally's 2014 third quarter discussion topic, "Mexico and Central America."

The portion of the North American mainland lying south of the United States consists of eight countries with close historical and cultural ties, yet there is no collective name for the region. "Central America" most commonly refers to the seven smaller nations, with Mexico excluded. "Mesoamerica" is a term used by anthropologists to describe an area that includes all of Central America plus just the southern part of Mexico. "Middle America" is a region that encompasses not only Mexico and Central America but all of the Caribbean nations as well.

Any way you look at it, Mexico dominates the region. It has almost four times the land area and almost three times the population of the seven Central American nations combined. There is an even greater preponderance, however, when it comes to internationally-known writers and artists. Is sheer size alone responsible for Mexico's prominence, or are there other factors?

Another question you might address in your reading is something that may come to mind as you look at a map of the region: Why is Central America a collection of seven little countries--all speaking the same language*--instead of one or two bigger ones? What separates and distinguishes these countries... geography? indigenous peoples? external forces? And how are these elements reflected in the literature of Central America?

(* Belize is a former British colony, but more of its citizens speak Spanish than English.)

Contents

The background material presented here is organized by country. Two sections are devoted to Mexico because of its size and literary prominence. We begin, however, with a short essay on the pre-Columbian and colonial history of the region in general. Each section includes links to books and other resources for your reading.

The authors profiled for each country are only those whose works are available in English translation. There are many, many more important authors from each country whose works can be found only in Spanish.

Introduction and Contents

Pre-Columbian History and European Conquest

Mexico - History

Mexico - Literature

Belize

Costa Rica

El Salvador

Guatemala

Honduras

Nicaragua

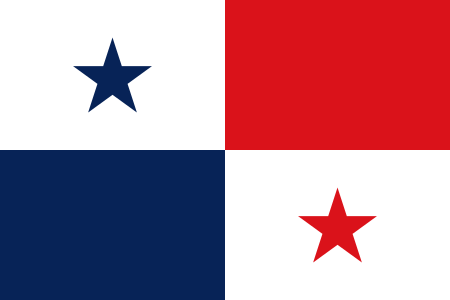

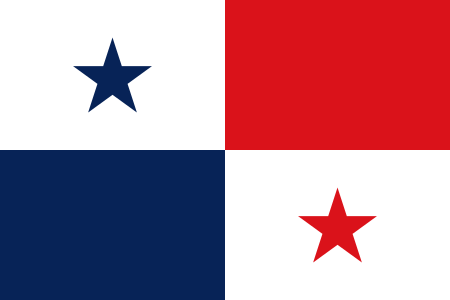

Panama

Themes to Look for in Your Reading

General History

A Brief History of Central America by Lynn V. Foster.

Central America: A Nation Divided by Ralph Lee Woodward is probably the most comprehensive history of the region and commonly used as a college text. The 3rd edition was published 1999.

The History of Central America by Thomas L. Pearcy is a short but fairly current (2005) history of the region.

Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America by Walter LeFeber tells the story of American intervention in the region up through the Iran-Contra affair.

Memory of Fire by Eduardo Galeano presents an emotionally-charged view of Latin American history in the form of short, anecdotal chapters.

Sons of the Shaking Earth by Eric Wolf is a classic history of Mesoamerica focusing on the influence of pre-Columbian cultures on the development of Mexico and Guatemala.

Understanding Central America: Global Forces, Rebellion and Change by John A. Booth and others. This recently-updated history focuses on the external forces that have shaped Central America.

Regional Anthologies

And We Sold the Rain: Contemporary Fiction from Central America edited by Rosario Santos.

Clamor of Innocence: Stories from Central America edited by Barbara Paschke and David Volpendesta.

Contemporary Short Stories from Central America edited by Leland H. Chambers.

(The work of Mexican and Central American authors can also be found in almost any of the many anthologies of Latin American poetry and prose.)

Literary Criticism and Reference

Writing Women in Central America: Gender & Fictionalization of History edited by Laura Barbas-Rhoden.

Web Resources

20th Century Prose Fiction: Central America, a brief essay from the U.S. Library of Congress "Handbook of Latin American Studies."

Handbook of Latin American Studies, U.S. Library of Congress, is an extensive scholarly bibliographic database of works from and about Latin America. Note that most works cited are in Spanish.

A Selective Guide to the Literature on Central America is the extensive bibliography from Central America: A Nation Divided by Ralph Lee Woodward with hundreds of books listed by category with commentary.

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: Central America provides an extensive discussion of authors from each country.

Welcome to Reading Globally's 2014 third quarter discussion topic, "Mexico and Central America."

The portion of the North American mainland lying south of the United States consists of eight countries with close historical and cultural ties, yet there is no collective name for the region. "Central America" most commonly refers to the seven smaller nations, with Mexico excluded. "Mesoamerica" is a term used by anthropologists to describe an area that includes all of Central America plus just the southern part of Mexico. "Middle America" is a region that encompasses not only Mexico and Central America but all of the Caribbean nations as well.

Any way you look at it, Mexico dominates the region. It has almost four times the land area and almost three times the population of the seven Central American nations combined. There is an even greater preponderance, however, when it comes to internationally-known writers and artists. Is sheer size alone responsible for Mexico's prominence, or are there other factors?

Another question you might address in your reading is something that may come to mind as you look at a map of the region: Why is Central America a collection of seven little countries--all speaking the same language*--instead of one or two bigger ones? What separates and distinguishes these countries... geography? indigenous peoples? external forces? And how are these elements reflected in the literature of Central America?

(* Belize is a former British colony, but more of its citizens speak Spanish than English.)

Contents

The background material presented here is organized by country. Two sections are devoted to Mexico because of its size and literary prominence. We begin, however, with a short essay on the pre-Columbian and colonial history of the region in general. Each section includes links to books and other resources for your reading.

The authors profiled for each country are only those whose works are available in English translation. There are many, many more important authors from each country whose works can be found only in Spanish.

Introduction and Contents

Pre-Columbian History and European Conquest

Mexico - History

Mexico - Literature

Belize

Costa Rica

El Salvador

Guatemala

Honduras

Nicaragua

Panama

Themes to Look for in Your Reading

General History

A Brief History of Central America by Lynn V. Foster.

Central America: A Nation Divided by Ralph Lee Woodward is probably the most comprehensive history of the region and commonly used as a college text. The 3rd edition was published 1999.

The History of Central America by Thomas L. Pearcy is a short but fairly current (2005) history of the region.

Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America by Walter LeFeber tells the story of American intervention in the region up through the Iran-Contra affair.

Memory of Fire by Eduardo Galeano presents an emotionally-charged view of Latin American history in the form of short, anecdotal chapters.

Sons of the Shaking Earth by Eric Wolf is a classic history of Mesoamerica focusing on the influence of pre-Columbian cultures on the development of Mexico and Guatemala.

Understanding Central America: Global Forces, Rebellion and Change by John A. Booth and others. This recently-updated history focuses on the external forces that have shaped Central America.

Regional Anthologies

And We Sold the Rain: Contemporary Fiction from Central America edited by Rosario Santos.

Clamor of Innocence: Stories from Central America edited by Barbara Paschke and David Volpendesta.

Contemporary Short Stories from Central America edited by Leland H. Chambers.

(The work of Mexican and Central American authors can also be found in almost any of the many anthologies of Latin American poetry and prose.)

Literary Criticism and Reference

Writing Women in Central America: Gender & Fictionalization of History edited by Laura Barbas-Rhoden.

Web Resources

20th Century Prose Fiction: Central America, a brief essay from the U.S. Library of Congress "Handbook of Latin American Studies."

Handbook of Latin American Studies, U.S. Library of Congress, is an extensive scholarly bibliographic database of works from and about Latin America. Note that most works cited are in Spanish.

A Selective Guide to the Literature on Central America is the extensive bibliography from Central America: A Nation Divided by Ralph Lee Woodward with hundreds of books listed by category with commentary.

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: Central America provides an extensive discussion of authors from each country.

2StevenTX

Pre-Columbian History and European Conquest

When Christopher Columbus and other European explorers first surveyed the coast of Central America and Mexico in the very early 16th century they found an assortment of indigenous cultures ranging in sophistication from hunter-gatherers to mighty empires. Humans had first settled the area at least 9,000 years earlier, and successive waves of migration and conquest had resulted in a complex mixture of cultures and languages.

The oldest and most advanced extant civilization was that of the Maya, centered on the Yucatan peninsula. Its roots go back to at least 2000 BCE, and Maya civilization had flowered from 250 to 900 CE. The Maya were the only Native American people to have a written language, and their achievements in architecture and the arts rivaled those of medieval Europe and Asia. The Maya were a community of city states with no single ruler or capital. By the time the Spaniards arrived, Maya civilization was in severe decline, with many of their cities already abandoned, but they were still strong enough to resist Spanish conquest for almost 200 years. They continue to survive as a people with many of their customs and beliefs intact.

The Aztec empire to the north was completely different from the Maya. The Mexica tribe arrived from the north in the central valley of Mexico around the year 1248 and founded their capital city of Tenochtitlan. They found a collection of city states based on the remains of the Toltec culture, which had flourished from 800 to 1000 CE. Through a succession of conquests and alliances, the Mexica built a loose empire of tribute-paying states. The name Aztec derives from the mythical place of origin of peoples like the Mexica speaking the Nahuatl language. The Aztecs were warriors, not builders. The great pyramids near their capital were built by a much earlier, unknown civilization. At their peak the Aztecs were a nation of 350,000 ruling an empire of at least 10 million people.

Columbus charted the coast of Central America on his fourth voyage in 1502. The first contact with the Maya--a violent one--was made in 1517. Two years later an expedition under Hernán Cortés with 11 ships and over 500 soldiers landed on the Yucatan peninsula. Here Cortés gained intelligence about the Aztec empire from an Aztec noblewoman who had become a Mayan slave. Marina, as Cortés called her, or Malinche as she is commonly known, became Cortés' interpreter and mistress. Under her guidance Cortés sailed his fleet to modern-day Veracruz where he was greeted by many Aztec subjects as a liberator. It was with the help of eager native allies that the tiny Spanish army was able to overthrow a nation larger and more populous than Spain itself.

After conquering the Aztecs, in 1524 Cortés led an expedition overland into present-day Honduras. The Maya, however, did not succumb as easily as the Aztecs, in spite of the ravages of smallpox and other European diseases. It would be several generations before the last bastion of Maya resistance, in present-day Guatemala, fell in 1697. The Maya continued, however, to be restive under Spanish, and later Mexican, rule with periodic uprisings even into the 20th century.

The Spanish conquistadors focused their attentions on the Aztec and Maya empires because that was where gold was to be found, but they eventually subjugated and began to colonize the entire region. Isolated pockets of independent native cultures remained, however, in regions too remote or forbidding to interest the Spanish. The Viceroyalty of New Spain, with its capital in Mexico City, was a region encompassing all of Mexico, all of Central America except Panama, and the western portion of what is now the United States. Panama, together with Colombia and Venezuela, comprised the Viceroyalty of New Granada. New Spain was administratively divided into colonies and regions called audencias, and that is where the names and identities of the various Central American nations and Mexican states originated, but they did not become separate political entities until after their independence from Spain.

The one exception to Spanish rule in the region was Belize. Originally ignored by the Spaniards, in the 1650s it became a base for English and Scottish pirates operating against Spanish shipping. The pirates supplemented their booty with legitimate income from logging, and eventually were given permission by Spanish authorities to remain as long as they refrained from piracy.

Intermarriage between the Spanish invaders and Native Americans was common, and by the 19th century and into the present most of population were mestizo, mixed race. Their folk culture likewise reflected a blending of European and Native elements. African slaves were also introduced to Mexico and other parts of the region by the Spanish and to Belize by the English. Slaves were used for mining and working sugar plantations, but slavery did not flourish in New Spain as it did in the Caribbean, English North America, and Brazil. Slavery was formally abolished when New Spain declared its independence from the mother country.

Books

Ancient Mexico & Central America: Archaeology and Culture History by Susan Toby Evans.

The Conquest of New Spain by Bernal Diaz del Castillo. Classic eyewitness account of the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs.

Daily Life of the Aztecs on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest by Jacques Soustelle.

Mesoamerican Voices: Native Language Writings from Colonial Mexico, Yucatan and Guatemala edited by Matthew Restall, Lisa Sousa, and Kevin Terraciano.

Mexico from the Olmecs to the Aztecs by Michael D. Coe

Popul Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings translated by Dennis Tedlock.

Web resources

The Ancient History Encyclopedia has extensive articles about the Aztecs and Maya civilizations. Search the site for articles on more specific topics such as language, art, religion, human sacrifice, etc.

The History Channel website has articles and online videos about the Maya and Aztecs

Aztec-History.com is a site created by a researcher who specializes in Aztec history.

Mesoweb: An Exploration of Mesoamerican Cultures is a resource site for students of pre-Columbian cultures.

Commentary on the Popul Vuh by Lewis Spence, 1908.

When Christopher Columbus and other European explorers first surveyed the coast of Central America and Mexico in the very early 16th century they found an assortment of indigenous cultures ranging in sophistication from hunter-gatherers to mighty empires. Humans had first settled the area at least 9,000 years earlier, and successive waves of migration and conquest had resulted in a complex mixture of cultures and languages.

The oldest and most advanced extant civilization was that of the Maya, centered on the Yucatan peninsula. Its roots go back to at least 2000 BCE, and Maya civilization had flowered from 250 to 900 CE. The Maya were the only Native American people to have a written language, and their achievements in architecture and the arts rivaled those of medieval Europe and Asia. The Maya were a community of city states with no single ruler or capital. By the time the Spaniards arrived, Maya civilization was in severe decline, with many of their cities already abandoned, but they were still strong enough to resist Spanish conquest for almost 200 years. They continue to survive as a people with many of their customs and beliefs intact.

The Aztec empire to the north was completely different from the Maya. The Mexica tribe arrived from the north in the central valley of Mexico around the year 1248 and founded their capital city of Tenochtitlan. They found a collection of city states based on the remains of the Toltec culture, which had flourished from 800 to 1000 CE. Through a succession of conquests and alliances, the Mexica built a loose empire of tribute-paying states. The name Aztec derives from the mythical place of origin of peoples like the Mexica speaking the Nahuatl language. The Aztecs were warriors, not builders. The great pyramids near their capital were built by a much earlier, unknown civilization. At their peak the Aztecs were a nation of 350,000 ruling an empire of at least 10 million people.

Columbus charted the coast of Central America on his fourth voyage in 1502. The first contact with the Maya--a violent one--was made in 1517. Two years later an expedition under Hernán Cortés with 11 ships and over 500 soldiers landed on the Yucatan peninsula. Here Cortés gained intelligence about the Aztec empire from an Aztec noblewoman who had become a Mayan slave. Marina, as Cortés called her, or Malinche as she is commonly known, became Cortés' interpreter and mistress. Under her guidance Cortés sailed his fleet to modern-day Veracruz where he was greeted by many Aztec subjects as a liberator. It was with the help of eager native allies that the tiny Spanish army was able to overthrow a nation larger and more populous than Spain itself.

After conquering the Aztecs, in 1524 Cortés led an expedition overland into present-day Honduras. The Maya, however, did not succumb as easily as the Aztecs, in spite of the ravages of smallpox and other European diseases. It would be several generations before the last bastion of Maya resistance, in present-day Guatemala, fell in 1697. The Maya continued, however, to be restive under Spanish, and later Mexican, rule with periodic uprisings even into the 20th century.

The Spanish conquistadors focused their attentions on the Aztec and Maya empires because that was where gold was to be found, but they eventually subjugated and began to colonize the entire region. Isolated pockets of independent native cultures remained, however, in regions too remote or forbidding to interest the Spanish. The Viceroyalty of New Spain, with its capital in Mexico City, was a region encompassing all of Mexico, all of Central America except Panama, and the western portion of what is now the United States. Panama, together with Colombia and Venezuela, comprised the Viceroyalty of New Granada. New Spain was administratively divided into colonies and regions called audencias, and that is where the names and identities of the various Central American nations and Mexican states originated, but they did not become separate political entities until after their independence from Spain.

The one exception to Spanish rule in the region was Belize. Originally ignored by the Spaniards, in the 1650s it became a base for English and Scottish pirates operating against Spanish shipping. The pirates supplemented their booty with legitimate income from logging, and eventually were given permission by Spanish authorities to remain as long as they refrained from piracy.

Intermarriage between the Spanish invaders and Native Americans was common, and by the 19th century and into the present most of population were mestizo, mixed race. Their folk culture likewise reflected a blending of European and Native elements. African slaves were also introduced to Mexico and other parts of the region by the Spanish and to Belize by the English. Slaves were used for mining and working sugar plantations, but slavery did not flourish in New Spain as it did in the Caribbean, English North America, and Brazil. Slavery was formally abolished when New Spain declared its independence from the mother country.

Books

Ancient Mexico & Central America: Archaeology and Culture History by Susan Toby Evans.

The Conquest of New Spain by Bernal Diaz del Castillo. Classic eyewitness account of the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs.

Daily Life of the Aztecs on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest by Jacques Soustelle.

Mesoamerican Voices: Native Language Writings from Colonial Mexico, Yucatan and Guatemala edited by Matthew Restall, Lisa Sousa, and Kevin Terraciano.

Mexico from the Olmecs to the Aztecs by Michael D. Coe

Popul Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings translated by Dennis Tedlock.

Web resources

The Ancient History Encyclopedia has extensive articles about the Aztecs and Maya civilizations. Search the site for articles on more specific topics such as language, art, religion, human sacrifice, etc.

The History Channel website has articles and online videos about the Maya and Aztecs

Aztec-History.com is a site created by a researcher who specializes in Aztec history.

Mesoweb: An Exploration of Mesoamerican Cultures is a resource site for students of pre-Columbian cultures.

Commentary on the Popul Vuh by Lewis Spence, 1908.

3StevenTX

Mexico

Population: 118,395,000

Capital: Mexico City

New Spain was the largest and richest of Spain's overseas possessions. The Europeans' primary focus was looting the region of its gold and silver. Converting the natives to Catholicism was secondary. The development of local industry was discouraged lest it compete with that of the mother country. Likewise the New Spaniards were prohibited from growing crops such as grapes and olives which might undermine Spanish agriculture. For three centuries, Spain's colonial policies kept one of the richest and most fertile regions of the world deliberately underdeveloped.

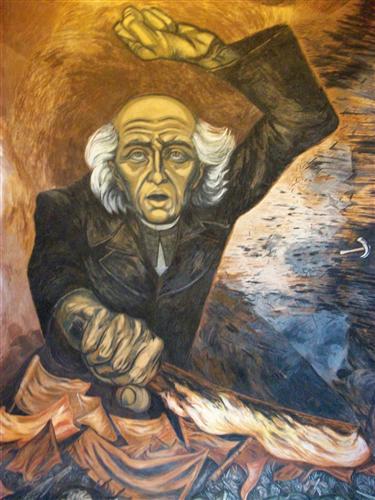

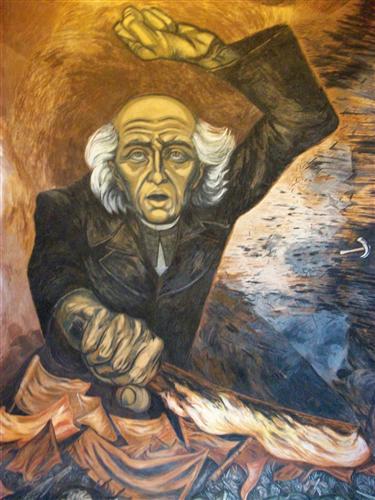

When Napoleon placed his brother on the Spanish throne in 1808 many Mexican leaders saw this as an opportunity to declare independence, but for different reasons. Conservatives resented the liberalizing Napoleonic policies that threatened the power of the aristocracy and the church. Liberals wanted to establish a democratic republic modeled after the United States. On September 16, 1810, (a date now celebrated as Mexico's Independence Day), a priest named Miguel Hidalgo led an uprising of peasants and miners against Spanish forces. The uneasy alliance of the far right and far left won initial success, but Napoleon's defeat in 1814 and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in Spain led to a prolonged conflict. It wasn't until 1821 that the full independence of New Spain was achieved.

Conservative factions took ownership of the revolution and established an Empire of Mexico, which included all of Central America with the exception of Panama and British Honduras (now Belize). Without popular support, the Empire collapsed in chaos in 1824. Mexico was declared a republic, while the colonies to the south organized themselves as the United Provinces of Central America.

The First Mexican Republic, 1824-1861, was an unstable period subject to conservative coups and liberal uprisings. Mexican history also began to be dominated by its land-hungry neighbor to the north. Texas, a Mexican state but settled by Anglo-Americans, declared its independence in 1836 and defeated an army led by Mexico's president. A decade later the United States annexed Texas and provoked a war with Mexico with the aim of grabbing more Mexican territory. Taking advantage of Mexico's internal divisions, a small American army landed at Veracruz and captured Mexico City in 1847, duplicating the feat of Hernán Cortés almost 300 years earlier. Mexico then agreed to sell to the U.S. for $15 million a vast territory including gold-rich California.

Struggles between conservatives and the church on one side, liberals and the poor on the other led to civil war in 1857. In 1861, with the United States busy fighting its own civil war, a consortium of conservative European states, led by France's Napoleon III, intervened with the ultimate aim of profiting commercially from control of Mexico's resources. With support from the church and most of Mexico's upper classes, a French army occupied Mexico City and installed a reluctant Austrian archduke, Maximilian, as Emperor of Mexico. The French never gained complete control of the country, and pulled out without protest in 1867 when a now-reunified United States threatened them with war. Maximilian was left behind to face a firing squad.

Mexico's president before and after French intervention, and the leader of its reform movement, was Benito Juárez. He championed the rights of indigenous peoples (being one himself), the separation of church and state, and the breakup of large estates and church lands. Juárez was opposed by conservatives including an army officer named Porfirio Díaz, who appointed himself president upon Juárez's death. Díaz ruled Mexico almost continually until 1911. The focus of his regime was law and order. Mexico achieved economic growth and stability, but at the expense of civil rights and the welfare of the lower classes. The reform laws of Benito Juárez were ignored, as the rich and the church retained ownership of most of the land. By 1910, dissent had broadened into open revolt, and the Mexican Revolution had begun.

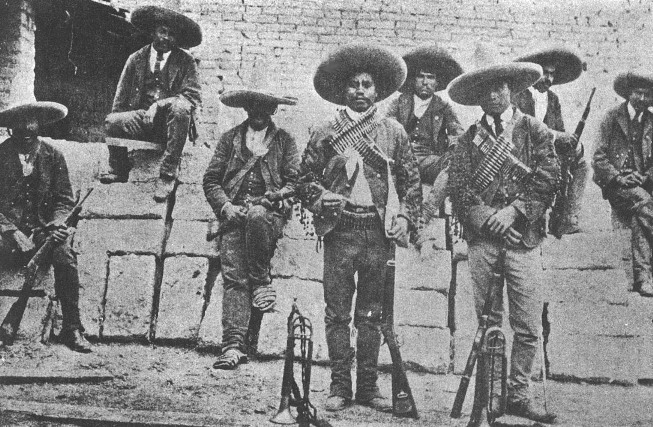

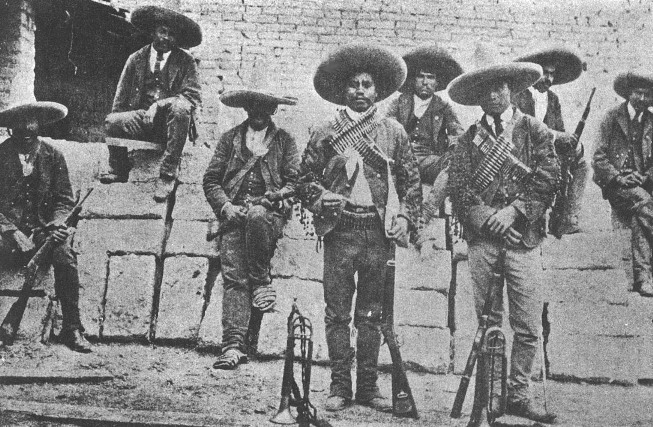

The Mexican Revolution was a confusing period of conflict between numerous factions and shifting alliances. Radical rebel leaders like Emiliano Zapata in the south and Pancho Villa in the north achieved the status of folk heroes, while a succession of leaders built short-lived coalitions that took control of the capital and the presidency. Four presidents and many rebel leaders including Zapata and Villa were either assassinated or executed before liberal forces established firm control over the country. The United States took an active role, bombarding Veracruz at one point and later sending an expedition into northern Mexico. Adventurers from America and elsewhere (including this writer's grandfather) joined the rebel forces, while thousands of Mexicans fled north into the United States to escape the violence and devastation.

Liberal forces established Mexico's current constitution in 1917, but did not secure full control of the country until 1920. Violence broke out again in 1926 when President Plutarco Elías Calles instituted harsh measures to crush the political power of the Catholic Church. The counter-revolution known as the Cristero War lasted until 1929, when peace was restored through negotiation.

In 1929 the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) won the presidency, ushering in an era of one-party rule that would last for the rest of the century. Through steps like nationalizing the oil industry the PRI managed to strengthen the economy while maintaining a liberal, secular government. Mexico joined the Allies in World War II, but played only a minor role. The chief impact of the war was the hundreds of thousands of Mexican agricultural workers who were welcomed into the United States to replace Americans drafted into service.

Though the PRI regime was often corrupt and at times dictatorial, it kept the army under control and was never seriously threatened by right-wing counter-revolutionaries. At a time when Spain and almost every Latin American country fell under the heel of military dictatorship, Mexico remained a haven for free expression in the Spanish-speaking world. Political exiles and refugee intellectuals from Europe and South America congregated in Mexico, enriching the already vibrant cultural environment.

Mexico was not without internal dissent, however. In the 1960s and 70s widespread dissatisfaction with economic disparity caused a number of leftist organizations to spring up in opposition to the government. In 1968, ten days before the opening of the Mexico City Olympic Games, students in the capital organized a protest against the suppression of political opposition. The government responded with force, and in what is now called the Tlatelolco Massacre, hundreds of students were killed by the military and police.

In the 21st century Mexico peacefully became a multi-party democracy. Conservatives held the presidency from 2000 to 2012 when the PRI was voted back into office. After overcoming several economic crises from 1970 to 1994, the country's biggest challenge now is the lawlessness and corruption spawned by the drug trade. High unemployment, the privatization of the oil industry, and the impact of America's immigration policies are major issues as well.

Books

The Course of Mexican History by Michael C. Meyer and others. This college history text is currently in its 9th edition.

Crafting Mexico: Intellectuals, Artisans and the State after the Revolution by Rick Anthony Lopez tells how the idea of Mexican nationhood was deliberately promoted through the arts.

Indian Women of Early Mexico edited by Susan Schroeder and others is a collection of essays on the influential roles played by native women in colonial women.

Insurgent Mexico by John Reed, an eyewitness account of the Mexican Revolution by the American journalist most famous for his book Ten Days that Shook the World.

Intervention!: The United States and the Mexican Revolution, 1913-1917 by John S. D. Eisenhower tells the little-known story of America's incursions onto Mexican soil during the Revolution.

Mexico: A Brief History by Alicia Hernández Chávez.

The Wind that Swept Mexico: The History of the Mexican Revolution 1910-1942 by Anita Brenner is a classic photographic history of the revolution.

Web resources

Geographia.com has essays on the geography and history of Mexico.

The History Channel has an extensive collections of articles and videos about Mexico's history and culture.

Mexconnect is primarily a travel website, but it has an extensive collection of articles on historical topics.

Mexico Maps - from the University of Texas Perry-Castañeda Map Collection. Note the link to the online Atlas of Mexico which has dozens of topographic, ethnographic, economic and historical maps.

Wikimedia Atlas of Mexico

Population: 118,395,000

Capital: Mexico City

New Spain was the largest and richest of Spain's overseas possessions. The Europeans' primary focus was looting the region of its gold and silver. Converting the natives to Catholicism was secondary. The development of local industry was discouraged lest it compete with that of the mother country. Likewise the New Spaniards were prohibited from growing crops such as grapes and olives which might undermine Spanish agriculture. For three centuries, Spain's colonial policies kept one of the richest and most fertile regions of the world deliberately underdeveloped.

When Napoleon placed his brother on the Spanish throne in 1808 many Mexican leaders saw this as an opportunity to declare independence, but for different reasons. Conservatives resented the liberalizing Napoleonic policies that threatened the power of the aristocracy and the church. Liberals wanted to establish a democratic republic modeled after the United States. On September 16, 1810, (a date now celebrated as Mexico's Independence Day), a priest named Miguel Hidalgo led an uprising of peasants and miners against Spanish forces. The uneasy alliance of the far right and far left won initial success, but Napoleon's defeat in 1814 and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in Spain led to a prolonged conflict. It wasn't until 1821 that the full independence of New Spain was achieved.

Conservative factions took ownership of the revolution and established an Empire of Mexico, which included all of Central America with the exception of Panama and British Honduras (now Belize). Without popular support, the Empire collapsed in chaos in 1824. Mexico was declared a republic, while the colonies to the south organized themselves as the United Provinces of Central America.

The First Mexican Republic, 1824-1861, was an unstable period subject to conservative coups and liberal uprisings. Mexican history also began to be dominated by its land-hungry neighbor to the north. Texas, a Mexican state but settled by Anglo-Americans, declared its independence in 1836 and defeated an army led by Mexico's president. A decade later the United States annexed Texas and provoked a war with Mexico with the aim of grabbing more Mexican territory. Taking advantage of Mexico's internal divisions, a small American army landed at Veracruz and captured Mexico City in 1847, duplicating the feat of Hernán Cortés almost 300 years earlier. Mexico then agreed to sell to the U.S. for $15 million a vast territory including gold-rich California.

Struggles between conservatives and the church on one side, liberals and the poor on the other led to civil war in 1857. In 1861, with the United States busy fighting its own civil war, a consortium of conservative European states, led by France's Napoleon III, intervened with the ultimate aim of profiting commercially from control of Mexico's resources. With support from the church and most of Mexico's upper classes, a French army occupied Mexico City and installed a reluctant Austrian archduke, Maximilian, as Emperor of Mexico. The French never gained complete control of the country, and pulled out without protest in 1867 when a now-reunified United States threatened them with war. Maximilian was left behind to face a firing squad.

Mexico's president before and after French intervention, and the leader of its reform movement, was Benito Juárez. He championed the rights of indigenous peoples (being one himself), the separation of church and state, and the breakup of large estates and church lands. Juárez was opposed by conservatives including an army officer named Porfirio Díaz, who appointed himself president upon Juárez's death. Díaz ruled Mexico almost continually until 1911. The focus of his regime was law and order. Mexico achieved economic growth and stability, but at the expense of civil rights and the welfare of the lower classes. The reform laws of Benito Juárez were ignored, as the rich and the church retained ownership of most of the land. By 1910, dissent had broadened into open revolt, and the Mexican Revolution had begun.

The Mexican Revolution was a confusing period of conflict between numerous factions and shifting alliances. Radical rebel leaders like Emiliano Zapata in the south and Pancho Villa in the north achieved the status of folk heroes, while a succession of leaders built short-lived coalitions that took control of the capital and the presidency. Four presidents and many rebel leaders including Zapata and Villa were either assassinated or executed before liberal forces established firm control over the country. The United States took an active role, bombarding Veracruz at one point and later sending an expedition into northern Mexico. Adventurers from America and elsewhere (including this writer's grandfather) joined the rebel forces, while thousands of Mexicans fled north into the United States to escape the violence and devastation.

Liberal forces established Mexico's current constitution in 1917, but did not secure full control of the country until 1920. Violence broke out again in 1926 when President Plutarco Elías Calles instituted harsh measures to crush the political power of the Catholic Church. The counter-revolution known as the Cristero War lasted until 1929, when peace was restored through negotiation.

In 1929 the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) won the presidency, ushering in an era of one-party rule that would last for the rest of the century. Through steps like nationalizing the oil industry the PRI managed to strengthen the economy while maintaining a liberal, secular government. Mexico joined the Allies in World War II, but played only a minor role. The chief impact of the war was the hundreds of thousands of Mexican agricultural workers who were welcomed into the United States to replace Americans drafted into service.

Though the PRI regime was often corrupt and at times dictatorial, it kept the army under control and was never seriously threatened by right-wing counter-revolutionaries. At a time when Spain and almost every Latin American country fell under the heel of military dictatorship, Mexico remained a haven for free expression in the Spanish-speaking world. Political exiles and refugee intellectuals from Europe and South America congregated in Mexico, enriching the already vibrant cultural environment.

Mexico was not without internal dissent, however. In the 1960s and 70s widespread dissatisfaction with economic disparity caused a number of leftist organizations to spring up in opposition to the government. In 1968, ten days before the opening of the Mexico City Olympic Games, students in the capital organized a protest against the suppression of political opposition. The government responded with force, and in what is now called the Tlatelolco Massacre, hundreds of students were killed by the military and police.

In the 21st century Mexico peacefully became a multi-party democracy. Conservatives held the presidency from 2000 to 2012 when the PRI was voted back into office. After overcoming several economic crises from 1970 to 1994, the country's biggest challenge now is the lawlessness and corruption spawned by the drug trade. High unemployment, the privatization of the oil industry, and the impact of America's immigration policies are major issues as well.

Books

The Course of Mexican History by Michael C. Meyer and others. This college history text is currently in its 9th edition.

Crafting Mexico: Intellectuals, Artisans and the State after the Revolution by Rick Anthony Lopez tells how the idea of Mexican nationhood was deliberately promoted through the arts.

Indian Women of Early Mexico edited by Susan Schroeder and others is a collection of essays on the influential roles played by native women in colonial women.

Insurgent Mexico by John Reed, an eyewitness account of the Mexican Revolution by the American journalist most famous for his book Ten Days that Shook the World.

Intervention!: The United States and the Mexican Revolution, 1913-1917 by John S. D. Eisenhower tells the little-known story of America's incursions onto Mexican soil during the Revolution.

Mexico: A Brief History by Alicia Hernández Chávez.

The Wind that Swept Mexico: The History of the Mexican Revolution 1910-1942 by Anita Brenner is a classic photographic history of the revolution.

Web resources

Geographia.com has essays on the geography and history of Mexico.

The History Channel has an extensive collections of articles and videos about Mexico's history and culture.

Mexconnect is primarily a travel website, but it has an extensive collection of articles on historical topics.

Mexico Maps - from the University of Texas Perry-Castañeda Map Collection. Note the link to the online Atlas of Mexico which has dozens of topographic, ethnographic, economic and historical maps.

Wikimedia Atlas of Mexico

4StevenTX

Mexico - Literature

Mexico City was one of the cultural capitals of the Hispanic world even before the nation of Mexico came into existence. The authors listed below are just the most prominent among hundreds whose work has achieved an international readership.

Authors

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651-1695), born in Mexico City, was the illegitimate daughter of a Spanish officer. A child prodigy and largely self-taught, she began composing religious poetry at age 8, and by her early teens had mastered Greek and was teaching Latin to other children. After serving as lady-in-waiting in the viceregal court, she rejected all offers of marriage and chose to enter a convent instead. Her writings combine religious, philosophical and feminist themes, and have been collected in a volume titled Poems, Protest, and a Dream: Selected Writings.

Mariano Azuela (1873-1952) was a physician and a follower of Pancho Villa. He wrote a number of novels and other works, mostly about the Mexican Revolution as he had seen it. His most famous work is The Underdogs (1915), the story of a peasant turned revolutionary.

Josefina Vicens (1911-1988) was a pioneer of Mexican experimental fiction, but is largely unknown because in her lifetime she shunned publicity and wrote under masculine pen names. Her novel The Empty Book is a metafictional work that poignantly addresses the unfulfilled hopes and unrealized dreams of everyday existence.

Octavio Paz (1914-1998, Nobel Prize 1990) is considered Mexico's most important modern poet. His existentialist poetry depicts the plight of the underprivileged and attempts to capture the essence of what is Mexican. Collections of his verse in English translation include The Collected Poems of Octavio Paz: 1957-1987. His best-known work, however, is a collection of essays on the Mexican identity titled Labyrinth of Solitude and Other Writings. Paz was left-leaning in his political views, but his rejection of revolutionary violence alienated him from many other intellectuals. From 1937 to 1959 he was married to the novelist Elena Garro.

Elena Garro (1916-1998) was a playwright and novelist from Puebla. Her first novel, Recollections of Things to Come, depicts the Cristero War, which she lived through, and is a commentary on the role of myth and illusion in our view of the past. She is considered by many to be the most important female writer in Mexico after Juana de la Cruz, but most of her work has remained untranslated. Garro was once married to the poet Octavio Paz, but in later life she became alienated not only from Paz but from Mexico's left-wing intellectual community in general. She went into self-exile in Paris where she died.

Juan Rulfo (1917-1986) was one of Mexico's most influential writers despite having published only two small books totaling fewer than 300 pages. Pedro Páramo, published in 1955, is a novel about a man who travels to his parents' home town only to find it inhabited by the specters of its dead residents. The novel was a major influence on Gabriel García Márquez and is considered the starting point of Latin American magical realism. Rulfo's short stories are collected in The Burning Plain and Other Stories.

Rosario Castellanos (1925-1974) was the daughter of a wealthy landowner from the state of Chiapas but was estranged from her family and sympathized with the region's poor Maya workers. Her parents died soon after being dispossessed of their land by the government, leaving Castellanos on her own while still in her teens. She associated with other intellectuals in Mexico City and supported herself by writing. Her most important work is The Book of Lamentations, a novel about a 19th century uprising of indigenous people in Chiapas. A sampling of her shorter work can be found in A Rosario Castellanos Reader. She was appointed Mexico's ambassador to Israel and died in Tel Aviv in 1974 from an accident which some consider to have been suicide.

Jorge Ibargüengoitia (1928-1983) was a very popular Mexican satirist from Guanajuato. The Lightning of August debunks the heroic myths of the Mexican Revolution. The Dead Girls is about a pair of sisters who ran a brothel in Ibargüengoitia's native state and were later discovered to have been serial killers. His other novels in translation include Two Crimes and Kill the Lion. Ibargüengoitia died in a major air disaster in Madrid in 1983.

Carlos Fuentes (1928-2012) was Mexico's most prominent novelist of recent decades. The son of a career diplomat, his exposure to other countries and cultures enabled him to look at Mexico and Latin America as an outsider would. Politically Fuentes was an outspoken leftist, but he refused to align himself with any party or regime. His first novel, Where the Air Is Clear was an instant success with its depiction of corruption and social inequality in Mexico. Fuentes's most celebrated novel, The Death of Artemio Cruz, uses innovating writing techniques to profile the development of modern Mexico through the thoughts of a dying man. His most ambitious work, Terra Nostra, attempts to encapsulate all of Hispanic history and culture in an immense literary structure that has been called Byzantine and Joycean.

Julieta Campos (1932-2007) was born in Cuba but acquired Mexican citizenship by marriage and is generally considered a Mexican writer. Her first novel, She Has Reddish Hair and Her Name Is Sabina, is a complex metafictional work in which the voices of various characters contend within the mind of a writer. In her experimental novel The Fear of Losing Eurydice, Campos explores various literary metaphors, in particular the idea that islands represent feelings of longing.

Elena Poniatowska (b. 1932) was born in Paris to a Polish-French father and Mexican mother. She moved to Mexico with her mother at age nine to escape German occupation and continues to live in Mexico City. Her work as a novelist and journalist has focused on the problems of women and the poor. Her most prominent work is La noche de Tlatelolco (transalted as Massacre in Mexico, an investigative report on the government's repression of student demonstrators in Mexico City in 1968. Here's to You, Jesusa! is a biographical novel about a working-class woman who participated in the Mexican Revolution.

Fernando del Paso (b. 1935) was born and educated in Mexico City but spent many years in London working for the BBC. His novels reflect Mexico's multi-cultural heritage. Palinuro of Mexico is a bizarre satire of Joycean complexity in which a pair of incestuous lovers explores a variety of cultural fantasies. News from the Empire is a work of historical fiction which explores the facts and myths about the lives of Emperor Maximilian and his wife Carlota.

José Emilio Pacheco (1939-2014) was considered Mexico's leading poet of the second half of the 20th century. His verse has been translated in Selected Poems of Pacheco. His shorter prose works are available in Battles in the Desert & Other Stories, which includes a nostalgic novella about Pacheco's childhood in the beautiful Mexico City neighborhood called "Colonia Roma."

Ángeles Mastretta (b. 1949) is a novelist, poet and journalist. Her novels such as Tear This Heart Out and Lovesick are romantic sagas with strong female characters set against important events in 20th century Mexican history. Women with Big Eyes is an autobiographical work about women who were important in her own life and based on stories Mastretta told her own daughter.

Paco Ignacio Taibo II (b. 1949) is a Spanish-born Mexican novelist and political activist who has written more than 50 books in various genres. Taibo's political works include 68, an examination of the government's violent suppression of student demonstrations in Mexico City in 1968. He is best known, however, for his series of detective novels such as An Easy Thing and No Happy Ending.

Laura Esquivel (b. 1950) became an instant celebrity with her 1989 novel+cookbook Like Water for Chocolate. Through culinary metaphors, it explores the conflict between modern and traditional family values during the Mexican Revolution. She has also written The Law of Love, a science fiction romance set in the 23rd century, and Malinche, a reinterpretation of the Aztec woman vilified by Mexicans for betraying her people to Hernán Cortés.

Francisco Rebolledo (b. 1950) was educated as a chemist and continues to combine scientific studies with cultural activities. He lives in the state of Morelos where he has been a university professor, researcher, editor, critic, and novelist. His only novel in English translation, Rasero, is the story of a Spanish diplomat in 18th-century France who has apocalyptic visions of the 20th century.

Alberto Ruy Sánchez (b. 1951) is a Mexico City writer and the founder and publisher of Mexico's leading arts magazine, Artes de Mexico. His writings draw upon his realization during a trip to Morocco how much Mexican culture draws upon Spain's Moorish heritage. His novels Mogador: The Names of the Air and The Secret Gardens of Mogador are both explorations of sensuality set in a Moroccan city.

Carmen Boullosa (b. 1954) is a writer who uses a range of forms and themes. Her novels include They're Cows, We're Pigs which uses the culture of Caribbean pirates to explore contrasting ideas of human organization. Cleopatra Dismounts is a feminist reconstruction of the life of Cleopatra that explores alternative views of her life. Leaving Tabasco is a coming-of-age novel that uses magical realism to illuminate the role of folklore in Mexican family life.

Enrique Serna (b. 1959) is a novelist who writes in a variety of genres and is highly regarded for his ability to capture local dialects and customs. His only novel currently in English translation is Fear of Animals, a crime thriller, but most of his more recent works have been historical fiction.

Cristina Rivera Garza (b. 1964) was born in Matamoros and is currently a professor at San Diego State University. Her novel No One Will See Me Cry is set in an insane asylum and depicts people on the margins of society during Mexico's turbulent 1920s.

Jorge Volpi (b. 1968) worked first as a lawyer before helping to found the "Crack Movement," a literary rebellion against the traditions of the Latin American Boom and magical realism. Volpi's novel In Search of Klingsor is a sophisticated thriller depicting the search for a Nazi nuclear scientist.

Anthologies

Best of Contemporary Mexican Fiction, edited by Álvaro Uribe, is a collection of stories by Mexican writers born since 1945.

Mexican Poetry: An Anthology, selected by Octavio Paz and translated by Samuel Beckett, is a collection representing 35 different poets from the 16th to the 19th centuries.

Mexico: A Traveler's Literary Companion edited by C. M. Mayo is a collection of short stories by Mexican authors organized geographically.

Mexico City Noir, edited by Paco Ignacio Taibo II, is a collection of modern crime fiction set in Mexico City.

Reversible Monuments: Contemporary Mexican Poetry edited by Monica de la Torre and Michael Wiegers is a huge bilingual collection of work by poets born after 1950, including poets writing in indigenous languages.

Web resources

Enciclopedia de la literatura en Mexico has biographical sketches of thousands of Mexican writers as well as other articles and features. There is no English-language version, but the site is very easy to navigate and glean basic information without knowing Spanish.

Mexican Literature and Authors from TheLatinoAuthor.com has capsule biographies of more than a dozen authors.

Terra Incognita: A Brief History of Mexican Science Fiction by Silvia Moreno-Garcia.

Mexico City was one of the cultural capitals of the Hispanic world even before the nation of Mexico came into existence. The authors listed below are just the most prominent among hundreds whose work has achieved an international readership.

Authors

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651-1695), born in Mexico City, was the illegitimate daughter of a Spanish officer. A child prodigy and largely self-taught, she began composing religious poetry at age 8, and by her early teens had mastered Greek and was teaching Latin to other children. After serving as lady-in-waiting in the viceregal court, she rejected all offers of marriage and chose to enter a convent instead. Her writings combine religious, philosophical and feminist themes, and have been collected in a volume titled Poems, Protest, and a Dream: Selected Writings.

Mariano Azuela (1873-1952) was a physician and a follower of Pancho Villa. He wrote a number of novels and other works, mostly about the Mexican Revolution as he had seen it. His most famous work is The Underdogs (1915), the story of a peasant turned revolutionary.

Josefina Vicens (1911-1988) was a pioneer of Mexican experimental fiction, but is largely unknown because in her lifetime she shunned publicity and wrote under masculine pen names. Her novel The Empty Book is a metafictional work that poignantly addresses the unfulfilled hopes and unrealized dreams of everyday existence.

Octavio Paz (1914-1998, Nobel Prize 1990) is considered Mexico's most important modern poet. His existentialist poetry depicts the plight of the underprivileged and attempts to capture the essence of what is Mexican. Collections of his verse in English translation include The Collected Poems of Octavio Paz: 1957-1987. His best-known work, however, is a collection of essays on the Mexican identity titled Labyrinth of Solitude and Other Writings. Paz was left-leaning in his political views, but his rejection of revolutionary violence alienated him from many other intellectuals. From 1937 to 1959 he was married to the novelist Elena Garro.

Elena Garro (1916-1998) was a playwright and novelist from Puebla. Her first novel, Recollections of Things to Come, depicts the Cristero War, which she lived through, and is a commentary on the role of myth and illusion in our view of the past. She is considered by many to be the most important female writer in Mexico after Juana de la Cruz, but most of her work has remained untranslated. Garro was once married to the poet Octavio Paz, but in later life she became alienated not only from Paz but from Mexico's left-wing intellectual community in general. She went into self-exile in Paris where she died.

Juan Rulfo (1917-1986) was one of Mexico's most influential writers despite having published only two small books totaling fewer than 300 pages. Pedro Páramo, published in 1955, is a novel about a man who travels to his parents' home town only to find it inhabited by the specters of its dead residents. The novel was a major influence on Gabriel García Márquez and is considered the starting point of Latin American magical realism. Rulfo's short stories are collected in The Burning Plain and Other Stories.

Rosario Castellanos (1925-1974) was the daughter of a wealthy landowner from the state of Chiapas but was estranged from her family and sympathized with the region's poor Maya workers. Her parents died soon after being dispossessed of their land by the government, leaving Castellanos on her own while still in her teens. She associated with other intellectuals in Mexico City and supported herself by writing. Her most important work is The Book of Lamentations, a novel about a 19th century uprising of indigenous people in Chiapas. A sampling of her shorter work can be found in A Rosario Castellanos Reader. She was appointed Mexico's ambassador to Israel and died in Tel Aviv in 1974 from an accident which some consider to have been suicide.

Jorge Ibargüengoitia (1928-1983) was a very popular Mexican satirist from Guanajuato. The Lightning of August debunks the heroic myths of the Mexican Revolution. The Dead Girls is about a pair of sisters who ran a brothel in Ibargüengoitia's native state and were later discovered to have been serial killers. His other novels in translation include Two Crimes and Kill the Lion. Ibargüengoitia died in a major air disaster in Madrid in 1983.

Carlos Fuentes (1928-2012) was Mexico's most prominent novelist of recent decades. The son of a career diplomat, his exposure to other countries and cultures enabled him to look at Mexico and Latin America as an outsider would. Politically Fuentes was an outspoken leftist, but he refused to align himself with any party or regime. His first novel, Where the Air Is Clear was an instant success with its depiction of corruption and social inequality in Mexico. Fuentes's most celebrated novel, The Death of Artemio Cruz, uses innovating writing techniques to profile the development of modern Mexico through the thoughts of a dying man. His most ambitious work, Terra Nostra, attempts to encapsulate all of Hispanic history and culture in an immense literary structure that has been called Byzantine and Joycean.

Julieta Campos (1932-2007) was born in Cuba but acquired Mexican citizenship by marriage and is generally considered a Mexican writer. Her first novel, She Has Reddish Hair and Her Name Is Sabina, is a complex metafictional work in which the voices of various characters contend within the mind of a writer. In her experimental novel The Fear of Losing Eurydice, Campos explores various literary metaphors, in particular the idea that islands represent feelings of longing.

Elena Poniatowska (b. 1932) was born in Paris to a Polish-French father and Mexican mother. She moved to Mexico with her mother at age nine to escape German occupation and continues to live in Mexico City. Her work as a novelist and journalist has focused on the problems of women and the poor. Her most prominent work is La noche de Tlatelolco (transalted as Massacre in Mexico, an investigative report on the government's repression of student demonstrators in Mexico City in 1968. Here's to You, Jesusa! is a biographical novel about a working-class woman who participated in the Mexican Revolution.

Fernando del Paso (b. 1935) was born and educated in Mexico City but spent many years in London working for the BBC. His novels reflect Mexico's multi-cultural heritage. Palinuro of Mexico is a bizarre satire of Joycean complexity in which a pair of incestuous lovers explores a variety of cultural fantasies. News from the Empire is a work of historical fiction which explores the facts and myths about the lives of Emperor Maximilian and his wife Carlota.

José Emilio Pacheco (1939-2014) was considered Mexico's leading poet of the second half of the 20th century. His verse has been translated in Selected Poems of Pacheco. His shorter prose works are available in Battles in the Desert & Other Stories, which includes a nostalgic novella about Pacheco's childhood in the beautiful Mexico City neighborhood called "Colonia Roma."

Ángeles Mastretta (b. 1949) is a novelist, poet and journalist. Her novels such as Tear This Heart Out and Lovesick are romantic sagas with strong female characters set against important events in 20th century Mexican history. Women with Big Eyes is an autobiographical work about women who were important in her own life and based on stories Mastretta told her own daughter.

Paco Ignacio Taibo II (b. 1949) is a Spanish-born Mexican novelist and political activist who has written more than 50 books in various genres. Taibo's political works include 68, an examination of the government's violent suppression of student demonstrations in Mexico City in 1968. He is best known, however, for his series of detective novels such as An Easy Thing and No Happy Ending.

Laura Esquivel (b. 1950) became an instant celebrity with her 1989 novel+cookbook Like Water for Chocolate. Through culinary metaphors, it explores the conflict between modern and traditional family values during the Mexican Revolution. She has also written The Law of Love, a science fiction romance set in the 23rd century, and Malinche, a reinterpretation of the Aztec woman vilified by Mexicans for betraying her people to Hernán Cortés.

Francisco Rebolledo (b. 1950) was educated as a chemist and continues to combine scientific studies with cultural activities. He lives in the state of Morelos where he has been a university professor, researcher, editor, critic, and novelist. His only novel in English translation, Rasero, is the story of a Spanish diplomat in 18th-century France who has apocalyptic visions of the 20th century.

Alberto Ruy Sánchez (b. 1951) is a Mexico City writer and the founder and publisher of Mexico's leading arts magazine, Artes de Mexico. His writings draw upon his realization during a trip to Morocco how much Mexican culture draws upon Spain's Moorish heritage. His novels Mogador: The Names of the Air and The Secret Gardens of Mogador are both explorations of sensuality set in a Moroccan city.

Carmen Boullosa (b. 1954) is a writer who uses a range of forms and themes. Her novels include They're Cows, We're Pigs which uses the culture of Caribbean pirates to explore contrasting ideas of human organization. Cleopatra Dismounts is a feminist reconstruction of the life of Cleopatra that explores alternative views of her life. Leaving Tabasco is a coming-of-age novel that uses magical realism to illuminate the role of folklore in Mexican family life.

Enrique Serna (b. 1959) is a novelist who writes in a variety of genres and is highly regarded for his ability to capture local dialects and customs. His only novel currently in English translation is Fear of Animals, a crime thriller, but most of his more recent works have been historical fiction.

Cristina Rivera Garza (b. 1964) was born in Matamoros and is currently a professor at San Diego State University. Her novel No One Will See Me Cry is set in an insane asylum and depicts people on the margins of society during Mexico's turbulent 1920s.

Jorge Volpi (b. 1968) worked first as a lawyer before helping to found the "Crack Movement," a literary rebellion against the traditions of the Latin American Boom and magical realism. Volpi's novel In Search of Klingsor is a sophisticated thriller depicting the search for a Nazi nuclear scientist.

Anthologies

Best of Contemporary Mexican Fiction, edited by Álvaro Uribe, is a collection of stories by Mexican writers born since 1945.

Mexican Poetry: An Anthology, selected by Octavio Paz and translated by Samuel Beckett, is a collection representing 35 different poets from the 16th to the 19th centuries.

Mexico: A Traveler's Literary Companion edited by C. M. Mayo is a collection of short stories by Mexican authors organized geographically.

Mexico City Noir, edited by Paco Ignacio Taibo II, is a collection of modern crime fiction set in Mexico City.

Reversible Monuments: Contemporary Mexican Poetry edited by Monica de la Torre and Michael Wiegers is a huge bilingual collection of work by poets born after 1950, including poets writing in indigenous languages.

Web resources

Enciclopedia de la literatura en Mexico has biographical sketches of thousands of Mexican writers as well as other articles and features. There is no English-language version, but the site is very easy to navigate and glean basic information without knowing Spanish.

Mexican Literature and Authors from TheLatinoAuthor.com has capsule biographies of more than a dozen authors.

Terra Incognita: A Brief History of Mexican Science Fiction by Silvia Moreno-Garcia.

5StevenTX

Belize

Population: 334,000

Capital: Belmopan

History

Modern-day Belize was part of the Mayan Yucatan before the Spanish arrived. Largely ignored by the conquistadors, the area remained under native control until well into the 17th century. Around 1650, English and Scottish pirates established a coastal refuge that would later become Belize City. They found that they could supplement their uncertain income from piracy by harvesting logwood, which was used to make dyes. Belize gradually grew into a permanent settlement and an unofficial English colony. As the settlers expanded their operations from the coast into the jungle, they came into conflict with the remaining Maya. Many Maya were taken as slaves and exported to other colonies such as Jamaica and the Carolinas. Eventually, as mahogany replaced logwood as the chief export, the English brought in large numbers of African slaves.

The Spanish considered Belize to be a part of Guatemala, and periodically attacked the English settlements here and elsewhere in the Yucatan region. On more than one occasion the buccaneers abandoned Belize altogether, only to return as soon as the Spanish moved on. The English government was reluctant to antagonize Madrid by officially supporting the colony. In 1779, when Spain joined the war with Great Britain over American independence, Belize was once again abandoned. But the Treaty of Paris in 1783 finally gave the British formal logging rights in the region, providing they would abstain from piracy and not compete with New Spain by growing plantation crops such as sugar cane.

When the rest of Central America gained its independence from Spain in the early 19th century, Belize was left a self-governing enclave under British oversight. It was not until 1862, however, that the colony was officially claimed by the British crown. The delay was due in large part to resistance from the United States, which had declared a "hands off" policy (the Monroe Doctrine) with regard to European interests in Central and South America. It was a costly war against the Maya which led to the establishment of the crown colony in 1862, at which time the United States was embroiled in its own civil war and unable to intervene. The new colony was named British Honduras.

The vicissitudes of the colony's single-product economy led to local landowners' selling off to overseas investors, and eventually the British Honduras Company emerged as the owner of most of the colony. Slavery had been abolished in all British colonies in 1833, but the exploitation of the labor force kept most of the population in severe poverty until well into the 20th century when workers won the right to unionize. When the British government granted its colonies higher level of local autonomy after World War II, this only strengthened the growing movement for independence. The picture was complicated, however, by Guatemala's increasingly assertive claim to British Honduras. But Guatemala's own civil war put an end to that threat. Mexico and other Latin American countries which had originally backed Guatemala's claim came around in the 1970s to support the independence of British Honduras. Under pressure from the United Nations, the United Kingdom finally granted Belize full independence in 1981.

Belize has a stable democratic government and, thanks to oil and tourism, one of the highest per capita incomes in Central America, but poverty and income disparity are major problems. Its population has seen huge changes because of emigration to the United States and immigration from other Central American countries. The "Kriol" population of descendants of African slaves, which used to be in the majority, is now outnumbered by Spanish-speaking immigrants from neighboring countries. English is still the official language, but is now spoken only by a minority of the population.

Authors

Colville N. Young (b. 1932) has been the Governor General of Belize since 1993. He has taken a leading role in promoting Belizean culture and literature, publishing books such as Creole Proverbs of Belize and Language and Education in Belize. His own fiction has been published as Pataki Full: Seven Belizean Short Stories.

Felicia Hernandez (b. 1932) moved to California but returned to Belize at the age of 65. Her work is autobiographical and focuses on the lives of women and children. Her works include the novel I Don't Know You But I Love You -- Write Me Letter? and the collection Those Ridiculous Years: And Other Garifuna Stories.

John Alexander Watler (b. 1938) is a performing storyteller and the author of a number of popular works with strong Belizean flavor. His novels include The Bomba Codex, a thriller about the smuggling of Maya artifacts through the jungles, Cry Among the Rain Clouds: The Belize Detective and The Snake Doctor: Drama on Chireno Beach.

Zee Edgell (b. 1940) is a Belizian writer, journalist and educator who now lives and teaches in the United States. Her 1982 novel Beka Lamb depicts the early nationalist movement in British Honduras through the eyes of a teenage girl.

Evan X. Hyde (b. 1947) is a writer and journalist who focuses on the lives and problems of Belizians of African descent. North Americakkkan Blues is an autobiographical work about his college years in Belize and at Dartmouth.

Zoila Ellis (b. 1957) is an attorney who begin writing poetry at age 8. She currently lives in the West Indies and has published a collection of short stories called On Heroes, Lizards and Passion.

Margaret Reynolds (b. 1971) is a Belizean nurse, the youngest of fourteen children, whose poetry addresses the problems of the urban poor and other themes. Her collected poetry to date is titled Reality & Beyond.

Anthologies

An Anthology of Belizean Literature: English, Creole, Spanish, Garifuna edited by Víctor Manuel Durán.

Memories, Dreams and Nightmares: A Short Story Anthology by Belizean Women Writers.

Of Words: An Anthology of Belizean Poetry edited by Michael D. Phillips.

Ping Wing Juk Me, Six Belizean Plays

Snapshots of Belize: An Anthology of Short Fiction edited by Leo Bradley and others.

Other books

Thirteen Chapters of a History of Belize by Assad Shoman is a highly regarded history of the country but out of print.

Web resources

BelizeNet is a portal to travel information about Belize. The site has a very nice multi-chapter illustrated online History of Belize.

TheLatinoAuthor.com has a page on Belizean Literature that describes the country's literary heritage and profiles a number of authors.

Belize Maps - from the University of Texas Perry-Castañeda Map Collection.

Wikimedia Atlas of Belize

Population: 334,000

Capital: Belmopan

History

Modern-day Belize was part of the Mayan Yucatan before the Spanish arrived. Largely ignored by the conquistadors, the area remained under native control until well into the 17th century. Around 1650, English and Scottish pirates established a coastal refuge that would later become Belize City. They found that they could supplement their uncertain income from piracy by harvesting logwood, which was used to make dyes. Belize gradually grew into a permanent settlement and an unofficial English colony. As the settlers expanded their operations from the coast into the jungle, they came into conflict with the remaining Maya. Many Maya were taken as slaves and exported to other colonies such as Jamaica and the Carolinas. Eventually, as mahogany replaced logwood as the chief export, the English brought in large numbers of African slaves.

The Spanish considered Belize to be a part of Guatemala, and periodically attacked the English settlements here and elsewhere in the Yucatan region. On more than one occasion the buccaneers abandoned Belize altogether, only to return as soon as the Spanish moved on. The English government was reluctant to antagonize Madrid by officially supporting the colony. In 1779, when Spain joined the war with Great Britain over American independence, Belize was once again abandoned. But the Treaty of Paris in 1783 finally gave the British formal logging rights in the region, providing they would abstain from piracy and not compete with New Spain by growing plantation crops such as sugar cane.

When the rest of Central America gained its independence from Spain in the early 19th century, Belize was left a self-governing enclave under British oversight. It was not until 1862, however, that the colony was officially claimed by the British crown. The delay was due in large part to resistance from the United States, which had declared a "hands off" policy (the Monroe Doctrine) with regard to European interests in Central and South America. It was a costly war against the Maya which led to the establishment of the crown colony in 1862, at which time the United States was embroiled in its own civil war and unable to intervene. The new colony was named British Honduras.

The vicissitudes of the colony's single-product economy led to local landowners' selling off to overseas investors, and eventually the British Honduras Company emerged as the owner of most of the colony. Slavery had been abolished in all British colonies in 1833, but the exploitation of the labor force kept most of the population in severe poverty until well into the 20th century when workers won the right to unionize. When the British government granted its colonies higher level of local autonomy after World War II, this only strengthened the growing movement for independence. The picture was complicated, however, by Guatemala's increasingly assertive claim to British Honduras. But Guatemala's own civil war put an end to that threat. Mexico and other Latin American countries which had originally backed Guatemala's claim came around in the 1970s to support the independence of British Honduras. Under pressure from the United Nations, the United Kingdom finally granted Belize full independence in 1981.

Belize has a stable democratic government and, thanks to oil and tourism, one of the highest per capita incomes in Central America, but poverty and income disparity are major problems. Its population has seen huge changes because of emigration to the United States and immigration from other Central American countries. The "Kriol" population of descendants of African slaves, which used to be in the majority, is now outnumbered by Spanish-speaking immigrants from neighboring countries. English is still the official language, but is now spoken only by a minority of the population.

Authors

Colville N. Young (b. 1932) has been the Governor General of Belize since 1993. He has taken a leading role in promoting Belizean culture and literature, publishing books such as Creole Proverbs of Belize and Language and Education in Belize. His own fiction has been published as Pataki Full: Seven Belizean Short Stories.

Felicia Hernandez (b. 1932) moved to California but returned to Belize at the age of 65. Her work is autobiographical and focuses on the lives of women and children. Her works include the novel I Don't Know You But I Love You -- Write Me Letter? and the collection Those Ridiculous Years: And Other Garifuna Stories.

John Alexander Watler (b. 1938) is a performing storyteller and the author of a number of popular works with strong Belizean flavor. His novels include The Bomba Codex, a thriller about the smuggling of Maya artifacts through the jungles, Cry Among the Rain Clouds: The Belize Detective and The Snake Doctor: Drama on Chireno Beach.

Zee Edgell (b. 1940) is a Belizian writer, journalist and educator who now lives and teaches in the United States. Her 1982 novel Beka Lamb depicts the early nationalist movement in British Honduras through the eyes of a teenage girl.

Evan X. Hyde (b. 1947) is a writer and journalist who focuses on the lives and problems of Belizians of African descent. North Americakkkan Blues is an autobiographical work about his college years in Belize and at Dartmouth.

Zoila Ellis (b. 1957) is an attorney who begin writing poetry at age 8. She currently lives in the West Indies and has published a collection of short stories called On Heroes, Lizards and Passion.

Margaret Reynolds (b. 1971) is a Belizean nurse, the youngest of fourteen children, whose poetry addresses the problems of the urban poor and other themes. Her collected poetry to date is titled Reality & Beyond.

Anthologies

An Anthology of Belizean Literature: English, Creole, Spanish, Garifuna edited by Víctor Manuel Durán.

Memories, Dreams and Nightmares: A Short Story Anthology by Belizean Women Writers.

Of Words: An Anthology of Belizean Poetry edited by Michael D. Phillips.

Ping Wing Juk Me, Six Belizean Plays

Snapshots of Belize: An Anthology of Short Fiction edited by Leo Bradley and others.

Other books

Thirteen Chapters of a History of Belize by Assad Shoman is a highly regarded history of the country but out of print.

Web resources

BelizeNet is a portal to travel information about Belize. The site has a very nice multi-chapter illustrated online History of Belize.

TheLatinoAuthor.com has a page on Belizean Literature that describes the country's literary heritage and profiles a number of authors.

Belize Maps - from the University of Texas Perry-Castañeda Map Collection.

Wikimedia Atlas of Belize

6StevenTX

Costa Rica

Population: 4,586,000

Capital: San José

History

Situated between the Maya and Inca areas of influence, Costa Rica was in a relatively primitive state of cultural development when the Spanish arrived, nor did the conquistadors pay much attention to a region where there was little silver or gold to be found. As the southernmost colony in New Spain and of little economic importance, Costa Rica was left to develop on its own. In 1719 it was described as "the poorest and most miserable colony in all of Spanish America."

But Costa Rica's poverty eventually worked in its favor, making it the most stable and peaceful country in the region. With no native labor force, and no incentive to import African slaves, the Spanish in Costa Rica were forced to work their own farms. As a result there was no aristocracy or underclass in the colony, but instead a steady growth of democratic institutions and values. Nor did Costa Ricans have to fight for their independence from Spain; it was won by faraway battles in Mexico. Coffee was introduced to Costa Rica in the mid-19th century and quickly became the country's most profitable crop, giving a much needed boost to the economy.

The biggest threat to Costa Rican independence came in 1856 when William Walker, the American filibusterer, invaded neighboring Nicaragua and attempted to establish a new empire for slavery in Central America. Costa Rica declared war against Walker's expedition, repelled an invasion by his army of Americans and Europeans, and then invaded Nicaragua and defeated Walker. The drummer boy Juan Santamaría, who gave his life in an heroic action that turned the tide of battle against Walker, is Costa Rica's national hero.