Teaching about the person and work of "Shakespeare" as done today amounts to a "crime"

ForumThe Globe: Shakespeare, his Contemporaries, and Context

Melde dich bei LibraryThing an, um Nachrichten zu schreiben.

1proximity1

Teaching about the person and work of "William Shakespeare" as it is done today amounts to a "crime"—and the students are its victims

____________________________________________

_______________________

Alas, no. The value in the humanities is surely to be found in and only in not merely "doing them," but, rather, doing them well. Otherwise, their value falls and fails in proportion to their being done poorly--or much, much worse than poorly.

With extremely few exceptions, around the world on every school-day students, from the primary-school grades through the baccalaureate-degree university level, are being taught a load of abject nonsense about the life and works of an author presented to them as responsible for the “Shakespeare” canon. These unsuspecting students are given to believe as a set of largely-ascertained facts what is actually sheer conjecture; and virtually all of it is grossly false, the product of centuries of “closed-shop” work held up as respectable scholarship.

They are not informed of even the existence of a now-centuries-old controversy over the real author's identity let alone the particulars of the controversy. That, I contend, ought to be recognized as constituting an educational fraud upon these students—in effect, hardly less than a “crime.”

If you are the parent of a student anywhere in age from eight to eighteen years old, you should be concerned that what your child is being taught about “William Shake-speare” of Stratford-Upon-Avon will eventually—if left unchallenged, as is nearly always the case—leave him or her with impediments to any kind of useful and interesting appreciation for the real author and his work. Rather than being enriched by this exposure to an imposture, your children, and, professors, your students, are being mislead and stunted in their intellectual growth, handed rank fables and told these are facts. In the end they are left with a confused picture and conception about a person who is simply irreconcilable with real life. No one has ever conformed to the image of the author as these students are given the life and (largely vacant) 'personality' “William Shakes-peare” to have been. In the end, most of them will leave their studies of Shakespeare under the impression that this author came to his work—about which, depending on the teacher's presentation, he was either passionate or, instead, almost indifferent—for no particular reason at all.

Why were so many of his plays set in ancient or contemporary Italy? Why did he choose to write plays in which the reigns of Kings John, Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, Richard III, Henry VI and Henry VIII are concerned rather than other Kings? Very simply, they'll have no idea and they may conclude that there needn't even have been any 'reason' since, as far as they are able to tell, these things just happen. Things turned out as they did; but they could have as easily turned out not only very differently but completely opposed to the way in which they happened to have occurred. If they are like most people, once their classroom treatments of Shakespeare have concluded, they'll leave them, never to return. They won't take up Shakespeare other than in a purely superficial way for the rest of their lives. Shakespeare will be for them at best and at most a trivial and passing amusement—nothing of any lasting importance and value, just one of many ways to spend a free hour and a half at a film or, perhaps, a staged production.

They will have no particular and coherent concept of the author or of anything which he “was trying to achieve”--nothing which informed his life-work, which they'll almost certainly see as being no different from any other playwright's work: just a way to make a living in a work-a-day world where drama is a means to entertainment and never more than that.

Now, it is of couse extremely likely that the above describes not only your own view of things—for you, like your child or your children, have fared no differently in the course of your education—but also that of your child's teachers and professors. They, too, almost certainly shall have travelled the same course and arrived at essentially the same end. Thus, many, perhaps most, of them are doing no other than what their own defrauded education has left them condemned to do: teach just as rotely and drearily as they were taught.

We are a scant few years from the centenary of the appearance of J. Thomas Looney's work, Shakespeare Identified in Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. It is this nearly one hundred year-old story which you were denied when you were at school and which your children are today, in their turn, being denied.

I am quite ready to defend academic freedom in both principle and practice. I do not believe that any teacher ought to be physically or morally forced to conform to an orthodoxy which outrages his or her sense of truth and fairness. But, for that very reason, I consider it a scandal that, in the world of Shakespeare scholarship, there are, one hundred years on from Looney's work, practically only those who teach the orthodox Shakespeare fraud standing at the front of the classroom and the lecture-hall, the auditorium. In a free and open academic arena, every teacher would, at a minimum, present the full scope of the issues surrounding the identity of the author and, beyond this, there'd also be just as many or perhaps a good deal more teachers teaching as the best-reading of the best-evidence the case according to which the rightful author is Edward, Earl of Oxford-- according to each individual teacher's leanings

There is today an initiative which goes by the name of “The Declaration of Reasonable Doubt.” It is the objective of those who subscribe to win a firm place in respectability for this idea that, on the merits, there exists ample ground and, indeed, more than ample ground to find that, as to the identity of William Shakespeare, author, the person from Stratford on Avon is of “doubtful” right.

To me, this is entirely too timid a stand. In fact and instead, the position stand facts on their head: there really is today no reasonable doubt as to the identity of the author: that author is, of couse, Edward, Earl of Oxford and about this there is no reasonable doubt left. Similarly, there is simply no remaining reasonable doubt about the person from Stratford, one William Shaksper. not having been the rightful author of any written line of a poem, a play or a sonnet.

You, dear paremts. in all likelihood, were defrauded in your education as far as “Shakespeare” 's work is concerned and today, your children, if you have any, are in their turn being similarly defrauded.

You have every reason and every right to object to this state of affairs. And so you ought to do.

__________________________

Where to turn to learn more----

If you weren't aware that there even existed a “Shakespeare authorship” question there is no reason to be surprised—this is precisely how orthodox Shakespeare teaching is supposed to work when it “succeeds” as intended. You're not supposed to be aware of the question or that it is a matter of controversy.

Now, having read this, you can turn to the following for a full treatment of the issues which the orthodox Shakespeare scholars would like you to ignore

An online “E-book” text of J. Thomas Looney's Shakespeare Identified in Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford (free download of the full text in a variety of formats.)

also, read a fully-developed exposition of the Shakespeare authorship question (SAQ) at the website of Stephanie Hopkins Hughes, “PoliticWorm” dot com : http://www.politicworm.com (www.politicworm.com ) Access to the site is free. (Readers who appreciate the work done there are welcome to make a voluntary donation.)

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________

"The humanities might ideally find justification simply in our doing them."

—Helen Small, (Oxford, 2013) The Value of the Humanities, Oxford University Press; p. 1.

_______________________

Alas, no. The value in the humanities is surely to be found in and only in not merely "doing them," but, rather, doing them well. Otherwise, their value falls and fails in proportion to their being done poorly--or much, much worse than poorly.

With extremely few exceptions, around the world on every school-day students, from the primary-school grades through the baccalaureate-degree university level, are being taught a load of abject nonsense about the life and works of an author presented to them as responsible for the “Shakespeare” canon. These unsuspecting students are given to believe as a set of largely-ascertained facts what is actually sheer conjecture; and virtually all of it is grossly false, the product of centuries of “closed-shop” work held up as respectable scholarship.

They are not informed of even the existence of a now-centuries-old controversy over the real author's identity let alone the particulars of the controversy. That, I contend, ought to be recognized as constituting an educational fraud upon these students—in effect, hardly less than a “crime.”

If you are the parent of a student anywhere in age from eight to eighteen years old, you should be concerned that what your child is being taught about “William Shake-speare” of Stratford-Upon-Avon will eventually—if left unchallenged, as is nearly always the case—leave him or her with impediments to any kind of useful and interesting appreciation for the real author and his work. Rather than being enriched by this exposure to an imposture, your children, and, professors, your students, are being mislead and stunted in their intellectual growth, handed rank fables and told these are facts. In the end they are left with a confused picture and conception about a person who is simply irreconcilable with real life. No one has ever conformed to the image of the author as these students are given the life and (largely vacant) 'personality' “William Shakes-peare” to have been. In the end, most of them will leave their studies of Shakespeare under the impression that this author came to his work—about which, depending on the teacher's presentation, he was either passionate or, instead, almost indifferent—for no particular reason at all.

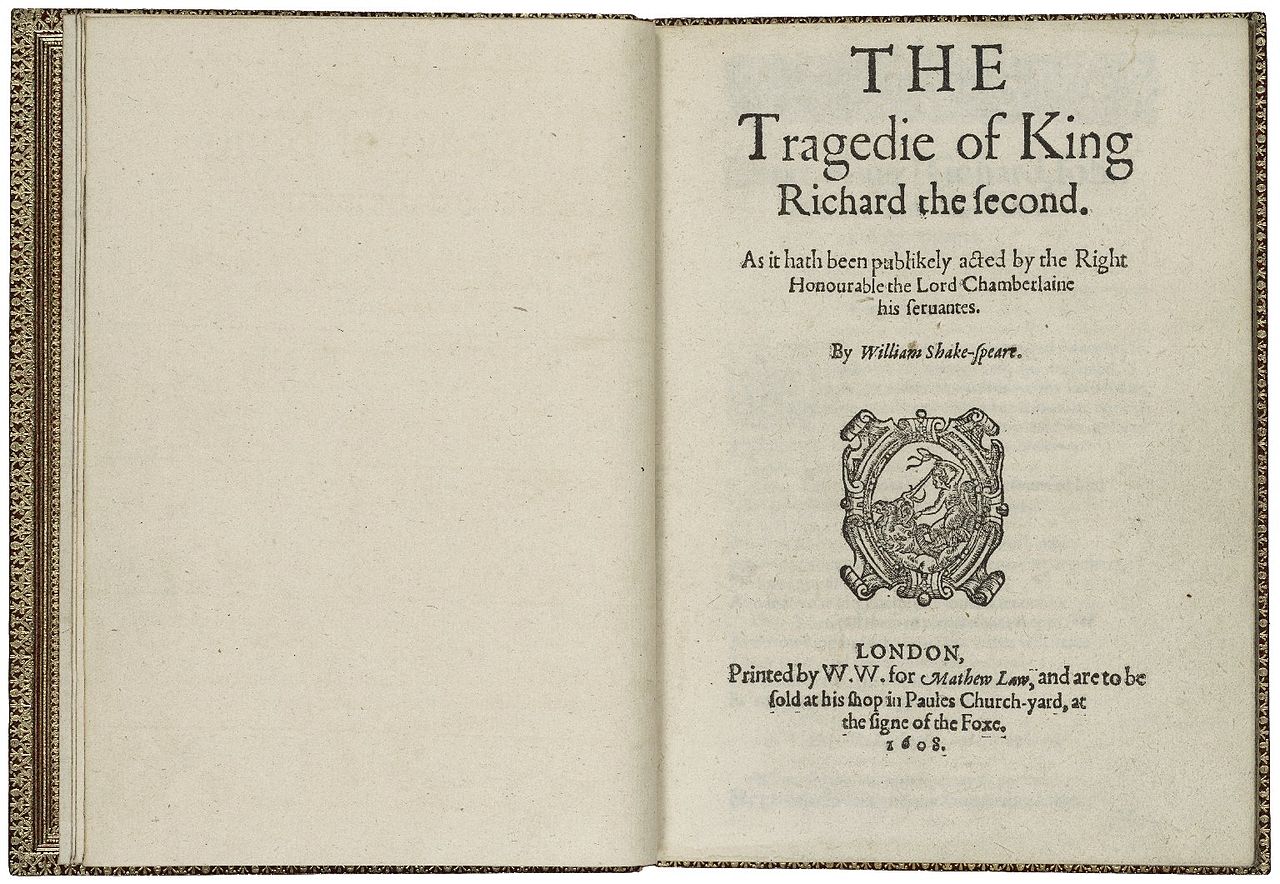

Why were so many of his plays set in ancient or contemporary Italy? Why did he choose to write plays in which the reigns of Kings John, Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, Richard III, Henry VI and Henry VIII are concerned rather than other Kings? Very simply, they'll have no idea and they may conclude that there needn't even have been any 'reason' since, as far as they are able to tell, these things just happen. Things turned out as they did; but they could have as easily turned out not only very differently but completely opposed to the way in which they happened to have occurred. If they are like most people, once their classroom treatments of Shakespeare have concluded, they'll leave them, never to return. They won't take up Shakespeare other than in a purely superficial way for the rest of their lives. Shakespeare will be for them at best and at most a trivial and passing amusement—nothing of any lasting importance and value, just one of many ways to spend a free hour and a half at a film or, perhaps, a staged production.

They will have no particular and coherent concept of the author or of anything which he “was trying to achieve”--nothing which informed his life-work, which they'll almost certainly see as being no different from any other playwright's work: just a way to make a living in a work-a-day world where drama is a means to entertainment and never more than that.

Now, it is of couse extremely likely that the above describes not only your own view of things—for you, like your child or your children, have fared no differently in the course of your education—but also that of your child's teachers and professors. They, too, almost certainly shall have travelled the same course and arrived at essentially the same end. Thus, many, perhaps most, of them are doing no other than what their own defrauded education has left them condemned to do: teach just as rotely and drearily as they were taught.

We are a scant few years from the centenary of the appearance of J. Thomas Looney's work, Shakespeare Identified in Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. It is this nearly one hundred year-old story which you were denied when you were at school and which your children are today, in their turn, being denied.

I am quite ready to defend academic freedom in both principle and practice. I do not believe that any teacher ought to be physically or morally forced to conform to an orthodoxy which outrages his or her sense of truth and fairness. But, for that very reason, I consider it a scandal that, in the world of Shakespeare scholarship, there are, one hundred years on from Looney's work, practically only those who teach the orthodox Shakespeare fraud standing at the front of the classroom and the lecture-hall, the auditorium. In a free and open academic arena, every teacher would, at a minimum, present the full scope of the issues surrounding the identity of the author and, beyond this, there'd also be just as many or perhaps a good deal more teachers teaching as the best-reading of the best-evidence the case according to which the rightful author is Edward, Earl of Oxford-- according to each individual teacher's leanings

There is today an initiative which goes by the name of “The Declaration of Reasonable Doubt.” It is the objective of those who subscribe to win a firm place in respectability for this idea that, on the merits, there exists ample ground and, indeed, more than ample ground to find that, as to the identity of William Shakespeare, author, the person from Stratford on Avon is of “doubtful” right.

To me, this is entirely too timid a stand. In fact and instead, the position stand facts on their head: there really is today no reasonable doubt as to the identity of the author: that author is, of couse, Edward, Earl of Oxford and about this there is no reasonable doubt left. Similarly, there is simply no remaining reasonable doubt about the person from Stratford, one William Shaksper. not having been the rightful author of any written line of a poem, a play or a sonnet.

You, dear paremts. in all likelihood, were defrauded in your education as far as “Shakespeare” 's work is concerned and today, your children, if you have any, are in their turn being similarly defrauded.

You have every reason and every right to object to this state of affairs. And so you ought to do.

__________________________

Where to turn to learn more----

If you weren't aware that there even existed a “Shakespeare authorship” question there is no reason to be surprised—this is precisely how orthodox Shakespeare teaching is supposed to work when it “succeeds” as intended. You're not supposed to be aware of the question or that it is a matter of controversy.

Now, having read this, you can turn to the following for a full treatment of the issues which the orthodox Shakespeare scholars would like you to ignore

An online “E-book” text of J. Thomas Looney's Shakespeare Identified in Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford (free download of the full text in a variety of formats.)

also, read a fully-developed exposition of the Shakespeare authorship question (SAQ) at the website of Stephanie Hopkins Hughes, “PoliticWorm” dot com : http://www.politicworm.com (www.politicworm.com ) Access to the site is free. (Readers who appreciate the work done there are welcome to make a voluntary donation.)

____________________________________________________

excerpted from Professor Richard Feynman's California Institute of Technology Commencement Address of 1974, "Cargo Cult Science" (.pdf file) :

_________________________

... ...

"But there is one feature I notice that is generally miss-

ing in Cargo Cult Science. That is the idea that we all hope

you have learned in studying science in school— we never ex-

plicitly say what this is, but just hope that you catch on by all

the examples of scientific investigation. It is interesting, there-

fore, to bring it out now and speak of it explicitly. It’s a kind

of scientific integrity, a principle of scientific thought that

corresponds to a kind of utter honesty-a kind of leaning over

backwards. For example, if you’re doing an experiment, you

should report everything that you think might make it in-

valid-not only what you think is right about it: other causes

that could possibly explain your results; and things you

thought of that you’ve eliminated by some other experiment,

and how they worked-to make sure the other fellow can tell

they have been eliminated.

"Details that could throw doubt on your interpretation must

be given, if you know them. You must do the best you can-

if you know anything at all wrong, or possibly wrong-to ex-

plain it. If you make a theory, for example, and advertise it,

or put it out, then you must also put down all the facts that

disagree with it, as well as those that agree with it. There is

also a more subtle problem. When you have put a lot of ideas

together to make an elaborate theory, you want to make sure,

when explaining what it fits, that those things it fits are not

just the things that gave you the idea for the theory; but that

the finished theory makes something else come out right, in

addition.

"In summary, the idea is to try to give all of the information

to help others to judge the value of your contribution; not

just the information that leads to judgment in one particular

direction or another.

"The easiest way to explain this idea is to contrast it, for ex-

ample, with advertising. Last night I heard that Wesson Oil

doesn’t soak through food. Well, that’s true. It’s not dishon-

est; but the thing I’m talking about is not just a matter of not

being dishonest, it’s a matter of scientific integrity, which is

another level. The fact that should be added to that advertis-

ing statement is that no oils soak through food, if operated at

a certain temperature. If operated at another temperature,

they all will-including Wesson Oil. So it’s the implication

which has been conveyed, not the fact, which is true, and the

difference is what we have to deal with.

"We’ve learned from experience that the truth will out.

Other experimenters will repeat your experiment and find

out whether you were wrong or right. Nature’s phenomena

will agree or they’ll disagree with your theory. And, although

you may gain some temporary fame and excitement, you will

not gain a good reputation as a scientist if you haven’t tried

to be very careful in this kind of work. And it’s this type of

integrity, this kind of care not to fool yourself, that is miss-

ing to a large extent in much of the research in Cargo Cult

Science.

"A great deal of their difficulty is, of course, the difficulty of

the subject and the inapplicability of the scientific method to

the subject. Nevertheless, it should be remarked that this is

not the only difficulty. That’s why the planes don’t land-but

they don’t land.

"We have learned a lot from experience about how to han-

dle some of the ways we fool ourselves. One example: Mil-

likan measured the charge on an electron by an experiment

with falling oil drops and got an answer which we now know

not to be quite right. It’s a little bit off, because he had the

incorrect value for the viscosity of air. It’s interesting to look

at the history of measurements of the charge of the electron,

after Millikan. If you plot them as a function of time, you

find that one is a little bigger than Millikan’s, and the next

one’s a little bit bigger than that, and the next one’s a little bit

bigger than that, until finally they settle down to a number

which is higher.

"Why didn’t they discover that the new number was higher

right away? It’s a thing that scientists are ashamed of-this

history-because it’s apparent that people did things like

this: When they got a number that was too high above Mil-

likan’s, they thought something must be wrong— and they

would look for and find a reason why something might be

wrong. When they got a number closer to Millikan’s value,

they didn’t look so hard. And so they eliminated the num-

bers that were too far off, and did other things like that.

We’ve learned those tricks nowadays, and now we don’t have

that kind of a disease.

"But this long history of learning how to not fool ourselves-

of having utter scientific integrity— is, I’m sorry to say, some-

thing that we haven’t specifically included in any particular

course that I know of. We just hope you’ve caught on by os-

mosis.

"The first principle is that you must not fool yourself-and

you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very

careful about that. After you’ve not fooled yourself, it’s easy

not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a

conventional way after that.

"I would like to add something that’s not essential to the sci-

entist, but something I kind of believe, which is that you

should not fool the layman when you’re talking as a scientist.

I am not trying to tell you what to do about cheating on your

wife, or fooling your girlfriend, or something like that, when

you’re not trying to be a scientist, but just trying to be an or-

dinary human being. We’ll leave those problems up to you

and your rabbi. I’m talking about a specific, extra type of in-

tegrity that is not lying, but bending over backwards to show

how you’re maybe wrong, that you ought to do when acting

as a scientist. And this is our responsibility as scientists, cer-

tainly to other scientists, and I think to laymen.

"For example, I was a little surprised when I was talking to a

friend who was going to go on the radio. He does work on

cosmology and astronomy, and he wondered how he would

explain what the applications of this work were. “Well,” I

said, “there aren’t any.” He said, “Yes, but then we won’t get

support for more research of this kind.” / think that’s kind of

dishonest. If you’re representing yourself as a scientist, then

you should explain to the layman what you’re doing— and if

they don’t want to support you under these circumstances,

then that’s their decision.

"One example of the principle is this: If you’ve made up

your mind to test a theory, or you want to explain some idea,

you should always decide to publish it whichever way it

comes out. If we only publish results of a certain kind, we can

make the argument look good. We must publish both kinds of

results." ... ...

4rolandperkins

"Edward, Earl of Oxford (as the author of "Shakespeare" .... there is no reasonable doubt." (1)

From what I have read of the Oxfordian point of view, I am focussed not so much on the premise that "the Stratford Man" COULD NOT have written the poems, sonnets and dramas, but that Oxford probably DID not write them. So I am left with the probability that while "Stratford" is probably not the author neither is Oxford.

What I find hard to believe is that Oxford, a noble, knowing

who the real Pericles was, would ever have named a non-Greek character

Pericles, Prince of Tyre. (Tyre, Phoenicia is in what is now Lebanon.) The Elizabethans were not experts on the Middle East; a little educated commoner would have been looking only for an exotic-sounding, ancient sounding, name, and might very well have so named a character.

In the Italian plays - - Romeo and Juliet,

Measure for Measure, and The Merchant of Venice, just as the supposed author, "Stratford" shows too little knowledge of the real Italy,

Oxford shows not enough. A commoner COULD have written those three plays.

Coriolanus and Jullius Caesar could have been

written by a commoner, indeed by anyone with a knowledge of Plutarchʻs not very reliable versions.

From what I have read of the Oxfordian point of view, I am focussed not so much on the premise that "the Stratford Man" COULD NOT have written the poems, sonnets and dramas, but that Oxford probably DID not write them. So I am left with the probability that while "Stratford" is probably not the author neither is Oxford.

What I find hard to believe is that Oxford, a noble, knowing

who the real Pericles was, would ever have named a non-Greek character

Pericles, Prince of Tyre. (Tyre, Phoenicia is in what is now Lebanon.) The Elizabethans were not experts on the Middle East; a little educated commoner would have been looking only for an exotic-sounding, ancient sounding, name, and might very well have so named a character.

In the Italian plays - - Romeo and Juliet,

Measure for Measure, and The Merchant of Venice, just as the supposed author, "Stratford" shows too little knowledge of the real Italy,

Oxford shows not enough. A commoner COULD have written those three plays.

Coriolanus and Jullius Caesar could have been

written by a commoner, indeed by anyone with a knowledge of Plutarchʻs not very reliable versions.

6proximity1

>4 rolandperkins:

"In the Italian plays - - Romeo and Juliet, Measure for Measure, and The Merchant of Venice, just as the supposed author, "Stratford" shows too little knowledge of the real Italy, Oxford shows not enough. A commoner COULD have written those three plays.

Coriolanus and Jullius Caesar could have been written by a commoner, indeed by anyone with a knowledge of Plutarchʻs not very reliable versions."

_______________

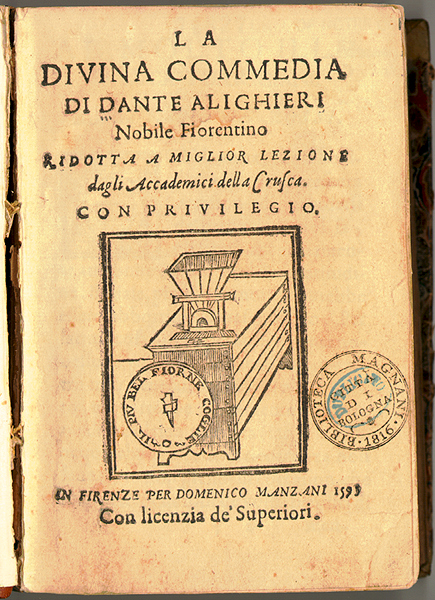

As for the plays set in Italy, Noemi Magri's collected essays on these plays, Such Fruits Out of Italy, (2014, Laugwitz Verlag, Buchholz, Germany; i.s.b.n. : 9783-933077-37-0) shows you are mistaken.

All of Oxford's references and allusions to places, modes of travel, styles of dress, art and architecture, etc., in Italy are shown to be correct and his detractors shown to have been ignorant of what Oxford knew fully accurately.

Perhaps you can explain, for example, how and why William Shaksper of Stratford should have known of and decided to make a completely gratuitous reference to an artist, Julio Romano, as "that rare Italian master, Julio Romano"... (The Winter's Tale V. ii. 94-9) / Magri, p. 44). This bit of knowledge is completely extraneous to the dramatic action and the plot of the play. Had it been left out, the play would in no way have been significantly changed. So it seems to be there for sheer "color". But it does not give the impression of being a labored insertion. Rather, it comes naturally in the course of a dialogue.

Are we to suppose that he learned of this by second-hand report from travellers come (or returned) to London? How does it happen that _all_ of his Italian aspects prove to be accurate--was he just incredibly lucky? Did he go around polling people to verify what he'd heard? How is it that he kept all this knowledge told him by firends or strangers and retrieved it so flawlessly--except for things which are rather obviously likely to be compositors' errors in making up type for printed quartos or the folio? Did he record everything in a notebook? If so, why does his use of these seem so completely fluid and unforced, rather than the product of an author's self-conscious and strained use of trivia added for effect--as other writers known to have done are criticizedf for as marring their work?

By the way, concerning using travellers' reports as a source of one's knowledge about the world beyond one's own travel experience, I cite the following, from Filippo De Vivo's Information and Communication in Venice : Rethinking Early Modern Politics (Oxford, 2007) p. 111:

"Contemporaries generally looked with suspicion at the information provided by such intermediaries. Writing for fellow merchants in the 1540s, Benedetti Cotrugli warned against giving credit to the reports of 'sailors' and 'travellers' who exaggerated out of drunkeness." (Cortugli 1990: 158)

The reference is to the 1990 edition Benedetto Cotrugli : Raguseo 'Il Libro dell'Arte di Mercatura (edited by Ugo Tucci) (TECHNÉ 9, (©1990) Arsenale Editrice in Venezia), First written in 1458, the text of Corugli was published in its principal editions in (Venice) 1573 (Oxford was 23 years old) and (Brescia) 1602.

at p. 158-59 one finds,

RE: "What I find hard to believe is that Oxford, a noble, knowing

who the real Pericles was, would ever have named a non-Greek character

Pericles, Prince of Tyre. (Tyre, Phoenicia is in what is now Lebanon.) The Elizabethans were not experts on the Middle East; a little educated commoner would have been looking only for an exotic-sounding, ancient sounding, name, and might very well have so named a character. "

What then is your argument? Just to be clear, are you contending that the name "Pericles" wouldn't have been used by Oxford (writing a play as 'Shakespeare' or under any other pen-name for that matter) because, a noble as well-versed in history as he was would simply never do such a thing--i.e. he'd know better than to make such a 'mistake'?

If not, why wouldn't he use the name?

My view is that, besides Oxford's having been the real author, whoever wrote the plays, as a person of such evident genius--and it's curiously schizophrenic: Stratfordians so easily shift from presenting Shakespeare as the unrivalled man of genius to Shakespeare, the ignorant dolt who couldn't tell which direction Milano is from Verona or Cremona from Milano, etc.--he didn't choose the name 'Pericles' and attach that name to a character as 'Prince of Tyre' out of ignorance, carelessnees, mistake or indifference -- and certainly not out of any ignorance of the fact that Tyre was located in Phoenicia, for example, and not in Greece or that there was a famous Athenian by the name of Pericles in the Athens of the Fifth century B.C. or that Alexander 'the Great' a Macedonian 'Greek' (in his cultural heritage) (Alexander III of Macedon) laid seige to Tyre in 332 B.C. about a century after Alexander had died.

He knew his history and, unlike what Stratfordians are so quick to suppose--depending on how it can serve their cause--he wasn't at times a liteary genius and at other times unable to think straight. We've all heard tales of people of acknowledged genius doing odd things; but these are typically things which relate to absent-mindedness in something which doesn't concern their professional practice. Thus, an Einstein can become confused about the direction to Mercer Street or a Kurt Gödel can secretly believe in fairies and sprites as real entities but in neither case did these things prevent them from thinking straight and clearly or imaginatively and creatively in their professed work. If Oxford used a historical name for a character and we find that character departing from strict historical facts as they were then believed or known to be, he has a very good and a very specific reason for doing so. And we ought to be interested in discovering what that reason is if it isn't already obvious since it is in such instances that we're apt to discover more confirmation for why the real authorship is Oxford's and not that Stratford fellow's. Indeed, when you get the author's identity correct it should and it does lead you to other as-yet-unrecognized facts about meanings and relationships between the author's times and his ideas and his work and the various people who perhaps had not previously been understood to have had some part in the author's life and work.

To their great credit, certain Stratfordian scholars--really the best among them--have been able to show how that is the case in the 'history plays' of Oxford as 'Shakespeare.'

So, until I hear more from you, I am not quite sure just how you mean to argue this point. But whatever it is, it's a point of importance to my purpose here.

"In the Italian plays - - Romeo and Juliet, Measure for Measure, and The Merchant of Venice, just as the supposed author, "Stratford" shows too little knowledge of the real Italy, Oxford shows not enough. A commoner COULD have written those three plays.

Coriolanus and Jullius Caesar could have been written by a commoner, indeed by anyone with a knowledge of Plutarchʻs not very reliable versions."

_______________

As for the plays set in Italy, Noemi Magri's collected essays on these plays, Such Fruits Out of Italy, (2014, Laugwitz Verlag, Buchholz, Germany; i.s.b.n. : 9783-933077-37-0) shows you are mistaken.

All of Oxford's references and allusions to places, modes of travel, styles of dress, art and architecture, etc., in Italy are shown to be correct and his detractors shown to have been ignorant of what Oxford knew fully accurately.

Perhaps you can explain, for example, how and why William Shaksper of Stratford should have known of and decided to make a completely gratuitous reference to an artist, Julio Romano, as "that rare Italian master, Julio Romano"... (The Winter's Tale V. ii. 94-9) / Magri, p. 44). This bit of knowledge is completely extraneous to the dramatic action and the plot of the play. Had it been left out, the play would in no way have been significantly changed. So it seems to be there for sheer "color". But it does not give the impression of being a labored insertion. Rather, it comes naturally in the course of a dialogue.

Are we to suppose that he learned of this by second-hand report from travellers come (or returned) to London? How does it happen that _all_ of his Italian aspects prove to be accurate--was he just incredibly lucky? Did he go around polling people to verify what he'd heard? How is it that he kept all this knowledge told him by firends or strangers and retrieved it so flawlessly--except for things which are rather obviously likely to be compositors' errors in making up type for printed quartos or the folio? Did he record everything in a notebook? If so, why does his use of these seem so completely fluid and unforced, rather than the product of an author's self-conscious and strained use of trivia added for effect--as other writers known to have done are criticizedf for as marring their work?

By the way, concerning using travellers' reports as a source of one's knowledge about the world beyond one's own travel experience, I cite the following, from Filippo De Vivo's Information and Communication in Venice : Rethinking Early Modern Politics (Oxford, 2007) p. 111:

"Contemporaries generally looked with suspicion at the information provided by such intermediaries. Writing for fellow merchants in the 1540s, Benedetti Cotrugli warned against giving credit to the reports of 'sailors' and 'travellers' who exaggerated out of drunkeness." (Cortugli 1990: 158)

The reference is to the 1990 edition Benedetto Cotrugli : Raguseo 'Il Libro dell'Arte di Mercatura (edited by Ugo Tucci) (TECHNÉ 9, (©1990) Arsenale Editrice in Venezia), First written in 1458, the text of Corugli was published in its principal editions in (Venice) 1573 (Oxford was 23 years old) and (Brescia) 1602.

at p. 158-59 one finds,

"Non debbeno, dando sé (1) ad li avisi di marinari et alcuni homini leggieri et viandanti, intraprehendere le cose grandi, perché lo marinaio constituito a cose grosse e d'intelletto ebete, ciò è debole, quando beve in taverna o compera pane in piazza che li paia che sia caro, ti porterà l'aviso che di vino et di pane in tale luogo si faria grande utile; non debbe lo moderato mercante, in spetiale quello che ha cura delle cose grandi, al adviso di colui intraprehendere di stesso con intellecto investigare soctilmente, havendo spesso in memoria quello egregio doctore di Lactantio:

'Oportet in ea re maxime in qua vite ratio versatur sibi quemque confidere suoque judicio ac propriis sensibus niti ad investigandum et perpetuandam veritatem, quam credentem alienis erroribus decipi tamquam ipsum rationis expertem dedit omnibus Deus pro virili sapientiam ut inaudita etiam investigare possent et audita perpendere.'

A french translation has this latin of Lactantio thus:

"VIII. Chacun doit se fier à soi-même dans la plus importante affaire de sa vie, et se servir de ses sens et de son esprit pour chercher la vérité, plutôt que de se laisser tromper en suivant les erreurs des autres. Dieu a donné à chaque homme une portion de lumière et de sagesse par laquelle il peut apprendre ce qu'il ignore et examiner ce qu'on lui propose."

http://remacle.org/bloodwolf/eglise/lactance/instit2.htm

(my translation):

"Each one must entrust to himself the most important matter in his life, and make use of sense and his wits in the searching for the truth rather than letting himself fall into error by following the errors of others. God grants each a portion of light and wisdom by which he may learn that of which he is ignorant and examine that which is proposed to him."

_____________________________

RE: "What I find hard to believe is that Oxford, a noble, knowing

who the real Pericles was, would ever have named a non-Greek character

Pericles, Prince of Tyre. (Tyre, Phoenicia is in what is now Lebanon.) The Elizabethans were not experts on the Middle East; a little educated commoner would have been looking only for an exotic-sounding, ancient sounding, name, and might very well have so named a character. "

What then is your argument? Just to be clear, are you contending that the name "Pericles" wouldn't have been used by Oxford (writing a play as 'Shakespeare' or under any other pen-name for that matter) because, a noble as well-versed in history as he was would simply never do such a thing--i.e. he'd know better than to make such a 'mistake'?

If not, why wouldn't he use the name?

My view is that, besides Oxford's having been the real author, whoever wrote the plays, as a person of such evident genius--and it's curiously schizophrenic: Stratfordians so easily shift from presenting Shakespeare as the unrivalled man of genius to Shakespeare, the ignorant dolt who couldn't tell which direction Milano is from Verona or Cremona from Milano, etc.--he didn't choose the name 'Pericles' and attach that name to a character as 'Prince of Tyre' out of ignorance, carelessnees, mistake or indifference -- and certainly not out of any ignorance of the fact that Tyre was located in Phoenicia, for example, and not in Greece or that there was a famous Athenian by the name of Pericles in the Athens of the Fifth century B.C. or that Alexander 'the Great' a Macedonian 'Greek' (in his cultural heritage) (Alexander III of Macedon) laid seige to Tyre in 332 B.C. about a century after Alexander had died.

He knew his history and, unlike what Stratfordians are so quick to suppose--depending on how it can serve their cause--he wasn't at times a liteary genius and at other times unable to think straight. We've all heard tales of people of acknowledged genius doing odd things; but these are typically things which relate to absent-mindedness in something which doesn't concern their professional practice. Thus, an Einstein can become confused about the direction to Mercer Street or a Kurt Gödel can secretly believe in fairies and sprites as real entities but in neither case did these things prevent them from thinking straight and clearly or imaginatively and creatively in their professed work. If Oxford used a historical name for a character and we find that character departing from strict historical facts as they were then believed or known to be, he has a very good and a very specific reason for doing so. And we ought to be interested in discovering what that reason is if it isn't already obvious since it is in such instances that we're apt to discover more confirmation for why the real authorship is Oxford's and not that Stratford fellow's. Indeed, when you get the author's identity correct it should and it does lead you to other as-yet-unrecognized facts about meanings and relationships between the author's times and his ideas and his work and the various people who perhaps had not previously been understood to have had some part in the author's life and work.

To their great credit, certain Stratfordian scholars--really the best among them--have been able to show how that is the case in the 'history plays' of Oxford as 'Shakespeare.'

So, until I hear more from you, I am not quite sure just how you mean to argue this point. But whatever it is, it's a point of importance to my purpose here.

7grayhog

"All of Oxford's references and allusions to places, modes of travel, styles of dress, art and architecture, etc., in Italy are show to be correct."

In TGoV Launce must hurry lest he lose the flood, so he grabs an oar to row out to the boat at anchorage and hop aboard before the vessels starts heading down the Adige.

His departure is also hurried lest he "lose the tide."

Launce, away, away, aboard! thy master is shipped

and thou art to post after with oars. What's the

matter? why weepest thou, man? Away, ass! You'll

lose the tide, if you tarry any longer.

The language seems to describe a tidal river, where an outbound voyage depends on everyone being aboard ship before the flood tide starts to ebb. Could you explain why Shakespeare was apparently incorrect on this point (since the Adige is not a tidal river)?

In TGoV Launce must hurry lest he lose the flood, so he grabs an oar to row out to the boat at anchorage and hop aboard before the vessels starts heading down the Adige.

His departure is also hurried lest he "lose the tide."

Launce, away, away, aboard! thy master is shipped

and thou art to post after with oars. What's the

matter? why weepest thou, man? Away, ass! You'll

lose the tide, if you tarry any longer.

The language seems to describe a tidal river, where an outbound voyage depends on everyone being aboard ship before the flood tide starts to ebb. Could you explain why Shakespeare was apparently incorrect on this point (since the Adige is not a tidal river)?

8proximity1

>7 grayhog:

Yes. I can cite what Magri writes in response to such an objection; and, if interested, you could actually get and read a copy of her work--this is really what I recommend. What's the use of my laboriously retyping for readers here the ample work cited done by thorough and careful scholars?

Her reply is at p. 100: "it often occurred in the past and still does now, though less frequently, that rain made the water level rise rapidly even within a few hours." ... "periods of low water (on the Adige) alternated (sporadically) with periods of "high tide". It's not known yet when exactly ...Oxford stayed in Verona; however, records report that in summer of 1575 the Adige was in flood."

Her text gives somewhat greater detail of the history of floods and the repair of earthworks, citing cases of major rain-induced floods from the 14th c. to the 16th c.

Closer to the coast, there is a tidal effect, (though much less dramatic than the sea coastal tides, it can be measured) upon rivers and their connecting canal ways--which, circa before and after 15-16 C., was even more evident than today due to more modern flood control works.

In addition, Oxford--the real author--in this as in so many instances, used puns and here,

"lose the tide" is meant in a multiple sense--and sets up the comedic answer

_______________________

(By the way, that happens to be the current circunstances in Tuscany, where the Arno's level is now, after a spate of protracted rain, quite high--though the river has not breached its banks in Florence.)

Yes. I can cite what Magri writes in response to such an objection; and, if interested, you could actually get and read a copy of her work--this is really what I recommend. What's the use of my laboriously retyping for readers here the ample work cited done by thorough and careful scholars?

Her reply is at p. 100: "it often occurred in the past and still does now, though less frequently, that rain made the water level rise rapidly even within a few hours." ... "periods of low water (on the Adige) alternated (sporadically) with periods of "high tide". It's not known yet when exactly ...Oxford stayed in Verona; however, records report that in summer of 1575 the Adige was in flood."

Her text gives somewhat greater detail of the history of floods and the repair of earthworks, citing cases of major rain-induced floods from the 14th c. to the 16th c.

Closer to the coast, there is a tidal effect, (though much less dramatic than the sea coastal tides, it can be measured) upon rivers and their connecting canal ways--which, circa before and after 15-16 C., was even more evident than today due to more modern flood control works.

In addition, Oxford--the real author--in this as in so many instances, used puns and here,

"lose the tide" is meant in a multiple sense--and sets up the comedic answer

PANTHINO

Away, ass, you'll lose

the tide, if you tarry any longer. (TG II.iii. 33-34)

LAUNCE

It is no matter if the tied were lost, for it is the

unkindest tied that ever any man tied.

PANTHINO

What's the unkindest tide?

LAUNCE

Why, he that's tied here, Crab, my dog.

PANTHINO

Tut, man, I mean thou'lt lose the flood; and,

in losing the flood, lose thy voyage; and, in losing thy

voyage, lose thy master; and, in losing thy master, lose

thy service; and, in losing thy service – Why dost thou

stop my mouth?

LAUNCE

For fear thou shouldst lose thy tongue.

PANTHINO

Where should I lose my tongue?

LAUNCE

In thy tale.

PANTHINO

In my tail!

LAUNCE

Lose the tide, and the voyage, and the master,

and the service, and the tied. Why, man, if the river

were dry, I am able to fill it with my tears. If the wind

were down, I could drive the boat with my sighs.

(TG II.iii. 35-51)

_______________________

(By the way, that happens to be the current circunstances in Tuscany, where the Arno's level is now, after a spate of protracted rain, quite high--though the river has not breached its banks in Florence.)

9grayhog

proximity1:

You cite Magri’s explanation for what the author meant by the word "flood" in TGoV. As you pointed out, she mentions that “in the summer of 1575 the Adige was in flood,” and later that “Sudden rains failing heavily throughout the year had caused the Adige and all its many tributaries to burst the banks and flood the countryside.” I'm sure, however, that Magri did not want us to think that Valentine and Speed would go sailing across the flooded countryside.

Magri, perhaps realizing the folly of cross-country sailing, pursues another tack, noting that "The Adige was dangerous for navigations in stormy weather or in spring when the snows in the Alps were thawing and large quantities of water made rivers and streams swollen. At times the current was so strong that ships were dashed against the bridge piers or stranded on the banks.” But this also seems a flawed proposal, given the cited dangers of navigating a river swollen by storms or the spring thaw.

So could you explain why Valentine and Speed would hurry to catch a real flood on the Adige when, in Magri’s own words, their ship could be “dashed against the bridge piers or stranded on the banks.” Rather, it seems that they should do the exact opposite. Instead of hurrying to catch the flood, they should wait out the danger, at least until the flood waters have subsided enough for safe navigation.

Magri then proceeds to claim the following lines show that Shakespeare “knew it was possible to suffer shipwreck while travelling on the Adige.”

Pro. Go, go, be gone, to save your ship from wrack,

Which cannot perish having thee aboard,

Being destin'd to a drier death on shore. (I,i)

But Magri seems to misread the line. It’s an allusion to the proverb, “He that is born to be hanged shall never be drowned.” Proteus is angry with Speed who bungled the delivery of Proteus’s love note to Julia. Hence the denunciation as Proteus sends Speed to catch Valentine before their ship heads downstream.

Thus Proteus’s line is not about an imminent “wrack” from foolishly hurrying to catch the swift currents of a flooded Adige. Actually, he means quite the opposite. He’s wishing, or perhaps predicting, that Speed will live long enough to eventually be hanged “on shore” for indolence (and bad puns) at some future time, effectively ensuring a safe passage for the entire voyage (not just the first few miles down the raging Adige, where they would not have ventured anyway), since the ship cannot perish with him aboard. Or do you hold with Magri that these lines are evidence of Shakespeare’s unique insight that the Adige, like every other river in the world, was dangerous to navigate after

heavy rains?

After you respond, perhaps we could also look at how Roe explains the meaning of the word “flood” in TGoV. His explanation is quite different from Magri’s.

And then we’ll need to examine the word “tide,” which is far more troubling than “flood,” as it shows even more clearly that the author did not know (or perhaps particularly care) about the hydrography of Verona.

BTW, I hope you have figured out that I do have both Magri and Roe. And a lot of other Oxfordian tomes. When I first stumbled onto the SAQ back in 2011, I found the Oxfordian case intriguing, but the more I learned, the more apparent it became that there’s no hard evidence for Oxford, not a single document, just supposition, idiosyncratic interpretation, and endless biographical correspondences (like Lear’s 3 daughters and the pirates). Yet there’s a wealth of contemporaneous documentary evidence for Stratford, for example the Grant of Arms to his father in 1598, which made his son, William, the only Mr. Shakespeare in town--just about the same time as the first mentions of Mr. Shakespeare appeared in the Parnassus plays where, like Meres, Shakespeare is mentioned repeatedly, while Oxford is mentioned only once, and off stage at that. But I digress.

So, again, why does Magri explain the playwright’s use of the word “flood” in a way that would send Valentine & Speed to almost certain disaster on the raging Adige?? And why does she believe Proteus’s curse demonstrates the author’s knowledge of shipwrecks on the Adige, and more important, why that would be such special knowledge?

Cheers! And I look forward to some lively--but respectful--discussions.

You cite Magri’s explanation for what the author meant by the word "flood" in TGoV. As you pointed out, she mentions that “in the summer of 1575 the Adige was in flood,” and later that “Sudden rains failing heavily throughout the year had caused the Adige and all its many tributaries to burst the banks and flood the countryside.” I'm sure, however, that Magri did not want us to think that Valentine and Speed would go sailing across the flooded countryside.

Magri, perhaps realizing the folly of cross-country sailing, pursues another tack, noting that "The Adige was dangerous for navigations in stormy weather or in spring when the snows in the Alps were thawing and large quantities of water made rivers and streams swollen. At times the current was so strong that ships were dashed against the bridge piers or stranded on the banks.” But this also seems a flawed proposal, given the cited dangers of navigating a river swollen by storms or the spring thaw.

So could you explain why Valentine and Speed would hurry to catch a real flood on the Adige when, in Magri’s own words, their ship could be “dashed against the bridge piers or stranded on the banks.” Rather, it seems that they should do the exact opposite. Instead of hurrying to catch the flood, they should wait out the danger, at least until the flood waters have subsided enough for safe navigation.

Magri then proceeds to claim the following lines show that Shakespeare “knew it was possible to suffer shipwreck while travelling on the Adige.”

Pro. Go, go, be gone, to save your ship from wrack,

Which cannot perish having thee aboard,

Being destin'd to a drier death on shore. (I,i)

But Magri seems to misread the line. It’s an allusion to the proverb, “He that is born to be hanged shall never be drowned.” Proteus is angry with Speed who bungled the delivery of Proteus’s love note to Julia. Hence the denunciation as Proteus sends Speed to catch Valentine before their ship heads downstream.

Thus Proteus’s line is not about an imminent “wrack” from foolishly hurrying to catch the swift currents of a flooded Adige. Actually, he means quite the opposite. He’s wishing, or perhaps predicting, that Speed will live long enough to eventually be hanged “on shore” for indolence (and bad puns) at some future time, effectively ensuring a safe passage for the entire voyage (not just the first few miles down the raging Adige, where they would not have ventured anyway), since the ship cannot perish with him aboard. Or do you hold with Magri that these lines are evidence of Shakespeare’s unique insight that the Adige, like every other river in the world, was dangerous to navigate after

heavy rains?

After you respond, perhaps we could also look at how Roe explains the meaning of the word “flood” in TGoV. His explanation is quite different from Magri’s.

And then we’ll need to examine the word “tide,” which is far more troubling than “flood,” as it shows even more clearly that the author did not know (or perhaps particularly care) about the hydrography of Verona.

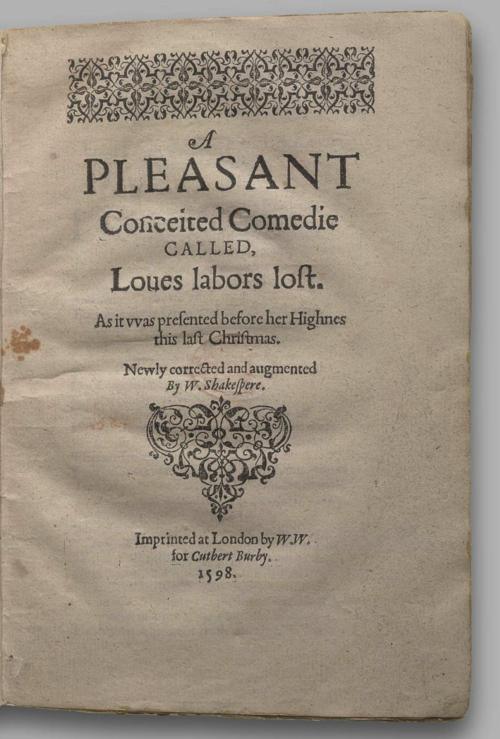

BTW, I hope you have figured out that I do have both Magri and Roe. And a lot of other Oxfordian tomes. When I first stumbled onto the SAQ back in 2011, I found the Oxfordian case intriguing, but the more I learned, the more apparent it became that there’s no hard evidence for Oxford, not a single document, just supposition, idiosyncratic interpretation, and endless biographical correspondences (like Lear’s 3 daughters and the pirates). Yet there’s a wealth of contemporaneous documentary evidence for Stratford, for example the Grant of Arms to his father in 1598, which made his son, William, the only Mr. Shakespeare in town--just about the same time as the first mentions of Mr. Shakespeare appeared in the Parnassus plays where, like Meres, Shakespeare is mentioned repeatedly, while Oxford is mentioned only once, and off stage at that. But I digress.

So, again, why does Magri explain the playwright’s use of the word “flood” in a way that would send Valentine & Speed to almost certain disaster on the raging Adige?? And why does she believe Proteus’s curse demonstrates the author’s knowledge of shipwrecks on the Adige, and more important, why that would be such special knowledge?

Cheers! And I look forward to some lively--but respectful--discussions.

10proximity1

>9 grayhog: "BTW, I hope you have figured out that I do have both Magri and Roe. And a lot of other Oxfordian tomes."

Good. Then, try and not only read them but understand them. You'll save me a world of unnecessary typing.

I will not read Magri or Roe aloud to you. I will recommend them to those who have an open mind on these matters. You're apparently reading (or you read ) them strictly for purposes of disparagement--decided on in advance.

Since you have Roe handy--and my copy has gone missing-- why don't you relate for us what Roe says about the meaning(s) of "flood" -- or, we could use our common sense and reason out how a poet, a master and ingenious inventor of metaphor such as Oxford was could and would use a term like "flood." My own view is that those who take "flood" in this scene to mean either strictly or especially the sense of the term as applied to such events as, for example, the famous

Johnstown Flood

are either being morons or are standard-issue Stratfordians --or both.

"So, again, why does Magri explain the playwright’s use of the word “flood” in a way that would send Valentine & Speed to almost certain disaster on the raging Adige?? And why does she believe Proteus’s curse demonstrates the author’s knowledge of shipwrecks on the Adige, and more important, why that would be such special knowledge?"

The answers to these are in the book you can apparently read---as in see and prounounce the words---but not really understand.

Here's a question for you-- and, like all others of your ilk, you'll ignore or dodge it:

Why didn't the great Shaksper's son-in-law, Dr. John Hall, mention his illustrious father in-law in his journals, hmm?

"Yet there’s a wealth of contemporaneous documentary evidence for Stratford, for example the Grant of Arms to his father in 1598, which made his son, William,"

this in no way indicates _any_ relationship to being literate, let alone being an accomplished poet and playwright. BUT YOU FUCKING KNEW THAT.

..."the only Mr. Shakespeare in town--just about the same time as the first mentions of Mr. Shakespeare appeared in the Parnassus plays where, like Meres, Shakespeare is mentioned repeatedly,"

added by those who were invested in disguising Oxford's authorship. of course.

I have a lot of other questions to which I'll bet you cannot--and so, shall not--give an honest and straight-forward answer. It seems apparent to me that you're here only for a fight, not to think fairly and reasonably. And, in that, you demonstrate for the information of others who aren't acquainted with their ugliness what Stratfordians, in their common type, look and act like. And, as such a specimen, you are welcome here. But as for your disingenuous questioning, we're done with that since it is abundantly clear you would not reciprocate any good-will shown on my part.

For example, above, I'd asked you, in my naive good-faith, this:

"What then is your argument? Just to be clear, are you contending that the name "Pericles" wouldn't have been used by Oxford (writing a play as 'Shakespeare' or under any other pen-name for that matter) because, a noble as well-versed in history as he was would simply never do such a thing--i.e. he'd know better than to make such a 'mistake'?"

You completely ignored it. You can now fuck off.

_______________________

Notice:

That figures.

________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________

***ETA*** IMPORTANT CORRECTION :

"grayhog" objects with good reason to my having taxed him for failing to reply to a call for clarification on a point about Oxford's use of the name "Pericles" for a prince of Tyre.

Indeed, he's correct. I confused RolandPerkins' post (>4 rolandperkins:) who, by thw way, also hasn't responded--but I don't put him in the company of grayhog on that account) with some of grayhog's disingenuous queries addressed to me. That's an error for which I am sorry and I make this correction to recognize my mistake.

On the other hand, see my appended reply at post No. 20 , below, concerning this fault of mine---where I'll answer later, at the first opportunity, other pertinent aspects of this:

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

Good. Then, try and not only read them but understand them. You'll save me a world of unnecessary typing.

I will not read Magri or Roe aloud to you. I will recommend them to those who have an open mind on these matters. You're apparently reading (or you read ) them strictly for purposes of disparagement--decided on in advance.

Since you have Roe handy--and my copy has gone missing-- why don't you relate for us what Roe says about the meaning(s) of "flood" -- or, we could use our common sense and reason out how a poet, a master and ingenious inventor of metaphor such as Oxford was could and would use a term like "flood." My own view is that those who take "flood" in this scene to mean either strictly or especially the sense of the term as applied to such events as, for example, the famous

Johnstown Flood

are either being morons or are standard-issue Stratfordians --or both.

"So, again, why does Magri explain the playwright’s use of the word “flood” in a way that would send Valentine & Speed to almost certain disaster on the raging Adige?? And why does she believe Proteus’s curse demonstrates the author’s knowledge of shipwrecks on the Adige, and more important, why that would be such special knowledge?"

The answers to these are in the book you can apparently read---as in see and prounounce the words---but not really understand.

Here's a question for you-- and, like all others of your ilk, you'll ignore or dodge it:

Why didn't the great Shaksper's son-in-law, Dr. John Hall, mention his illustrious father in-law in his journals, hmm?

"Yet there’s a wealth of contemporaneous documentary evidence for Stratford, for example the Grant of Arms to his father in 1598, which made his son, William,"

this in no way indicates _any_ relationship to being literate, let alone being an accomplished poet and playwright. BUT YOU FUCKING KNEW THAT.

..."the only Mr. Shakespeare in town--just about the same time as the first mentions of Mr. Shakespeare appeared in the Parnassus plays where, like Meres, Shakespeare is mentioned repeatedly,"

added by those who were invested in disguising Oxford's authorship. of course.

I have a lot of other questions to which I'll bet you cannot--and so, shall not--give an honest and straight-forward answer. It seems apparent to me that you're here only for a fight, not to think fairly and reasonably. And, in that, you demonstrate for the information of others who aren't acquainted with their ugliness what Stratfordians, in their common type, look and act like. And, as such a specimen, you are welcome here. But as for your disingenuous questioning, we're done with that since it is abundantly clear you would not reciprocate any good-will shown on my part.

For example, above, I'd asked you, in my naive good-faith, this:

"What then is your argument? Just to be clear, are you contending that the name "Pericles" wouldn't have been used by Oxford (writing a play as 'Shakespeare' or under any other pen-name for that matter) because, a noble as well-versed in history as he was would simply never do such a thing--i.e. he'd know better than to make such a 'mistake'?"

You completely ignored it. You can now fuck off.

_______________________

Notice:

Member: grayhog

Collections None

Reviews None

Tags None

Groups The Globe

Favorite authors Not set

Account type public, free

URLs /profile/grayhog (profile)

/catalog/grayhog (library)

Member since Feb 5, 2018

That figures.

________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________

***ETA*** IMPORTANT CORRECTION :

"grayhog" objects with good reason to my having taxed him for failing to reply to a call for clarification on a point about Oxford's use of the name "Pericles" for a prince of Tyre.

Indeed, he's correct. I confused RolandPerkins' post (>4 rolandperkins:) who, by thw way, also hasn't responded--but I don't put him in the company of grayhog on that account) with some of grayhog's disingenuous queries addressed to me. That's an error for which I am sorry and I make this correction to recognize my mistake.

On the other hand, see my appended reply at post No. 20 , below, concerning this fault of mine---where I'll answer later, at the first opportunity, other pertinent aspects of this:

"But, sadly, I guess you are declining what I had hoped would be some "lively--but respectful--discussions." You have showed your colors with this bit a nastiness: "I have a lot of other questions to which I'll bet you cannot--and so, shall not--give an honest and straight-forward answer." Punctuated with an unfortunate, "You can now fuck off," apparently because I did not answer a question about Pericles that was not even directed to me."

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

11proximity1

post >9 grayhog: is what comes from Stratfordians' somersaults in reason trying to find something amiss in Oxford's work as Shakespeare---and why? Because in this instance, it serves their partisan purpose to try and make the author out as a buffoon who used words carelessly at best and, at worst, in shocking ignorance since, of course, the assumption--correct, as a matter of fact--is that their candidate, unlike the real author, Oxford, never left England as far as we have any reason to believe. Thus, his depiction of Italian geography and modes of travel reveals him as ill-or uninformed, using only what he gathered from hearsay from travellers whose paths he crossed in London.

That is our otherwise supposed unrivalled literary genius as Stratfordians give him to us. Or else, some other person wrote the work-- for some, it was Francis Bacon. Now, then, does Bacon fit this fool's-profile? Does Sir Walter Ralegh?

"Flood" is used only twice in the entire play. Both times are found spoken by Panthino in the passage I already cited above in >8 proximity1:. Oxford varies the usage both earlier and later and writes, "tide" (in a rare usage refering to aquatic tides, since, usually, "tide" in early modern English referred nearly always to some aspect of "time"--and is related to "tidings": "betide", "e'en tide" "often tide").

But Oxford himself amswers "grayhog" 's disingenuous question about the use of flood:

Read the dialogue--- there's no prospect of a "flood" in the Johnston, PA. sense of the term:

PANTHINO

Tut, man, I mean thou'lt lose the flood, and, in

losing the flood, lose thy voyage, and, in losing

thy voyage, lose thy master, and, in losing thy

master, lose thy service, and, in losing thy

service,--Why dost thou stop my mouth?

Why "lose the flood"? If this were a life-threatening "flood" in the Johnstown sense, then Oxford would surely not have described "missing" it as a "loss". He'd have written, "Lose the flood and save thy life thereby" instead.

In addition why doesn't Launce 'wait out' "grayhog's" disingenuously posited perils of taking ship on the river?

My guess, from reading the dialogue is that there is no such peril:

Thus, " 'safe' for the master, 'safe' for his servant"--- and as a servant, under another's orders Launce doesn't have a choice to wait out a peril which, from the play's dialogue's indications, doesn't exist.

this is a comic scene. Oxford is having fun here in word-play and this is one of his most characteristic aspects of Oxford. We have absolutely nothing surviving in either his own or others' testimony about William Shaksper to indicate that he was of this kind of humor. On the contray to so much that is glaringly obvious about Oxford and his often displayed indifference or contempt for monetary wealth, Shakeper was a penny-pinching merchant and becaome "respectable" for no other reason than that wealth and what it allowed him to purchase.

Really! This is _very_ difficult stuff. And Stratfordians have simply bitten off more than they can chew in supposing that Oxford wrote for such like as their intellects. They're smitten with a Shakespeare fable, in love with it, and determined to shoe-horn this idiotic myth into the tiny thinking-spaces they possess. But that, yes, is a very task and it make them look like what they are: ridiculously desperate.

It also offers the rest of us an object-lesson in what computer programmers know and describe as the problem of "GIGO", the initials which refer to the phrase, "Garbge in, garbage out. Those four words pithily capture all that is wrong in orthodox Shakespeare teacher's ways, means and methods.

That is our otherwise supposed unrivalled literary genius as Stratfordians give him to us. Or else, some other person wrote the work-- for some, it was Francis Bacon. Now, then, does Bacon fit this fool's-profile? Does Sir Walter Ralegh?

"Flood" is used only twice in the entire play. Both times are found spoken by Panthino in the passage I already cited above in >8 proximity1:. Oxford varies the usage both earlier and later and writes, "tide" (in a rare usage refering to aquatic tides, since, usually, "tide" in early modern English referred nearly always to some aspect of "time"--and is related to "tidings": "betide", "e'en tide" "often tide").

But Oxford himself amswers "grayhog" 's disingenuous question about the use of flood:

Read the dialogue--- there's no prospect of a "flood" in the Johnston, PA. sense of the term:

PANTHINO

Tut, man, I mean thou'lt lose the flood, and, in

losing the flood, lose thy voyage, and, in losing

thy voyage, lose thy master, and, in losing thy

master, lose thy service, and, in losing thy

service,--Why dost thou stop my mouth?

Why "lose the flood"? If this were a life-threatening "flood" in the Johnstown sense, then Oxford would surely not have described "missing" it as a "loss". He'd have written, "Lose the flood and save thy life thereby" instead.

In addition why doesn't Launce 'wait out' "grayhog's" disingenuously posited perils of taking ship on the river?

My guess, from reading the dialogue is that there is no such peril:

Scene III The same. A street.

... ... ...

Enter PANTHINO

PANTHINO

Launce, away, away, aboard! thy master is shipped

and thou art to post after with oars. What's the

matter? why weepest thou, man? Away, ass! You'll

lose the tide, if you tarry any longer.

Thus, " 'safe' for the master, 'safe' for his servant"--- and as a servant, under another's orders Launce doesn't have a choice to wait out a peril which, from the play's dialogue's indications, doesn't exist.

LAUNCE

"Lose the tide, and the voyage, and the master,

and the service, and the tied. Why, man, if the river

were dry, I am able to fill it with my tears. If the wind

were down, I could drive the boat with my sighs."

this is a comic scene. Oxford is having fun here in word-play and this is one of his most characteristic aspects of Oxford. We have absolutely nothing surviving in either his own or others' testimony about William Shaksper to indicate that he was of this kind of humor. On the contray to so much that is glaringly obvious about Oxford and his often displayed indifference or contempt for monetary wealth, Shakeper was a penny-pinching merchant and becaome "respectable" for no other reason than that wealth and what it allowed him to purchase.

Really! This is _very_ difficult stuff. And Stratfordians have simply bitten off more than they can chew in supposing that Oxford wrote for such like as their intellects. They're smitten with a Shakespeare fable, in love with it, and determined to shoe-horn this idiotic myth into the tiny thinking-spaces they possess. But that, yes, is a very task and it make them look like what they are: ridiculously desperate.

It also offers the rest of us an object-lesson in what computer programmers know and describe as the problem of "GIGO", the initials which refer to the phrase, "Garbge in, garbage out. Those four words pithily capture all that is wrong in orthodox Shakespeare teacher's ways, means and methods.

12proximity1

>9 grayhog:

"Cheers! And I look forward to some lively--but respectful--discussions."

Now, see there? This is the sign-off from a fellow (man or woman) who has just tried to engage in a disingenuous game of "Gotcha!" And he (or she, but I suppose it's "he") is now trying to bullshit us--not only bullshit me, but the rest of you, readers, as well--that he's now ready for "some lively--but respectful--discussions."

In falsely representing himself as in need of another's (mine, in this case) time and trouble in relating for him the details of a text which, supposedly, he doesn't have, when, in fact, he has the text and could have instead started by quoting from it and asking his questions in a straight-forward manner, he loses, forfeits the "respectful discussion" he claims to want to have.

Would you trust such a fellow after this?

Again, this is typical of the disingenuous bullshit to which Stratfordians consistently treat Oxfordians. My sentiments are no secret here when it comes to Oxford's part as "Shakespeare." I don't play games of "Gotcha!" and people who do demonstrate their moral standards.

RE:

Asking this blantantly-loaded question--which reminds me of "Do you still beat your wife?"-kind-of-questions-- is also typical. Magri in no way " "explain(s) the playwright’s use of the word 'flood' in a way that would send Valentine & Speed to almost certain disaster on the raging Adige" Instead, in pages 95 to 100 she writes generally of the fact that water-travel between Verona and Milano by river and canal-connections was common. After that exposition, during which the term "flood" doesn't appear, she goes into the potential perils of this type of travel:

(p. 101) "Owing to the flow rate and the steep gradient of the riverbed, the Adige was (i.e. could be) dangerous for navigation in stormy weather or in Spring when the snows in the Alps were thawing and large quantities of water made rivers and streams swollen. At times the current was so strong that ships were dashed against the bridge piers or stranded on the banks."

That's all. This is in direct response to Stratfordians' long-standing objections that the Adige doesn't know anything of "tidal" effects --which is only true in the most picky strict sense, since it does in effect have irregular rises and drops in rate and height which are similar for watercraft to a coast's tide changes. There's no reference in any of this to Oxford's two uses of "flood" in Panthino's lines.

Then, following that she takes up, separately the fact that, yes, river and canal-boat travel, due to many factors, including bad weather, storms, heavy rains, sudden changes in the currents' strengths, does indeed pose inherent risks to travellers aboard barges and sail-driven craft, and offers this, her opinion,

"These facts would account for Proteus's words after Speed has left the stage, 'Go, go, be gone, to save your ship from wreck, (sic) ("wrack" in the First Folio) which cannot perish having thee aboard, Being destin'd to a drier death on shore. (I, i, 142-144)

(the next paragrahph has minor revisions from a previous version)

That comment can and may refer to simply a feature of the inherent dangers in such travel in those times and conditions. It is not at all necessary that it besome claim that due to "the author" 's intention to present us with a scene in which he has set his characters on some particularly and imminently perilous river journey; there is nothing else in the dialogue to support such an interpretation. Nor is there any reason to suppose either that Magri interpreted the author's use of "flood" in the way "Grayhog" claims or that the author himself intended that interpretation be drawn by the reader/play-audience.

"Grayhog" claims that here, the author is alluding to an old adage and using it cleverly to cast aspersions on Speed. That's of course quite possible and, as a conjecture, it's both interesting and worthy of mention. But there is, as far as I'm aware, simply no documented basis for supposing that our Shaksper of Stratford had ever known or used the adage--though of course he might have. Had it been Oxford's source, he could have known and read of it in its 14th century French version--since he was fluent in French and could easily have seen it in a text or heard it among members in Cecil's--or his own-- household growing up: "Noyer ne peut cil qui doit pendre." ( from The Facts on File Dictionary of Proverbs by Martin H. Manser)

So "grayhog" is raising an assinine question, posed full of disingenuousness and invites us, after doing this, to take him at his word when he writes,

"Cheers! And I look forward to some lively--but respectful--discussions."

Like hell he is! He has all the texts he needs to understand these things. Instead of using them for that, he uses them to come here and try and engage in games of "Gotcha!"

With that, I am really quite done with this person's bullshit. But I consider this exchange a useful example and I'm sure to make further reference to it as an example when I discuss how Stratfordians typically argue and reason.

Notice, for example, that, when it's a matter of the intellectual potential of the Stratford William Shaksper, we're invited by Stratfordians to marvel at his genius--and that genius, it happens, is only "available" to us as evidence of his being Shakespeare, the literary genius, if we already grant as a given fact that this Shaksper fellow from Stratford was the genius they, Stratfordians claim he had to have been---because his plays show that. If you're dizzy from this circular reasoning, I do not blame you.

Notice, too, how these same people who can draw circles to prove that Shaskper of Stratford had to have written the plays because he was a genius--as is indicated by his having written the plays, these same don't hesitate to make Oxford out as a blunderer---and this is proven by the many errors in his plays.

Well, Magri's book of collected essays is devoted to exploding those charges of errors about Italian geography, history, culture, and modes of living. And it does that brilliantly.

But unless an Oxfordian first brings up her work, no Stratfordian will mention her.

That tells us something about Stratfordians and it isn't flattering.

"Cheers! And I look forward to some lively--but respectful--discussions."