SassyLassy Sallies On

ForumClub Read 2020

Melde dich bei LibraryThing an, um Nachrichten zu schreiben.

1SassyLassy

New Year, New Decade - time to sally forth.

However, my annual thread start with Pantone's colour of the year is not quite so energetic. In a real change from last year's Living Coral, we now have Classic Blue, designed says the company to give us ... a solid and dependable hue we can always rely on", something that "...provides an anchoring foundation." Snooze.

The company then picks up the pace, saying "Classic Blue encourages us to look beyond the obvious to expand our thinking; challenging us to think more deeply, increase our perspective and open the flow of communication"

I'm all for thinking more deeply in the new year, and hope that at least some of my reading will reflect and encourage that, but for the rest, this year's choice just doesn't do it for me. Bring back Radiant Orchid (2014) or Emerald (2013). They provide stimulation at least!

However, my annual thread start with Pantone's colour of the year is not quite so energetic. In a real change from last year's Living Coral, we now have Classic Blue, designed says the company to give us ... a solid and dependable hue we can always rely on", something that "...provides an anchoring foundation." Snooze.

The company then picks up the pace, saying "Classic Blue encourages us to look beyond the obvious to expand our thinking; challenging us to think more deeply, increase our perspective and open the flow of communication"

I'm all for thinking more deeply in the new year, and hope that at least some of my reading will reflect and encourage that, but for the rest, this year's choice just doesn't do it for me. Bring back Radiant Orchid (2014) or Emerald (2013). They provide stimulation at least!

2SassyLassy

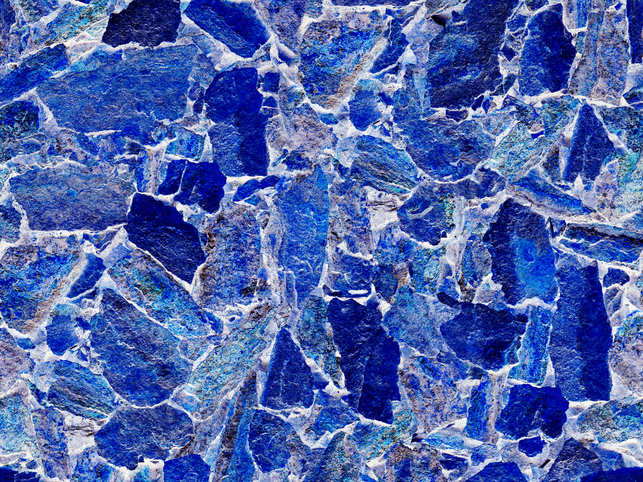

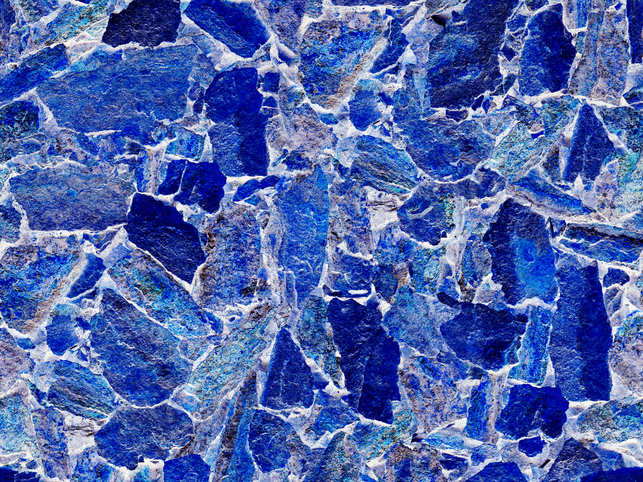

Here are some slightly better takes on the colour from other sources:

from CBS News

from jetfreshflowers

from economic times.india times

from CBS News

from jetfreshflowers

from economic times.india times

3SassyLassy

Well every year lately I bemoan my previous year's reading in terms of quantity, so 2019 will be no different. It came in at 50 books. I do tend to read longer books and don't use audiobooks, but there is still no reason for reading so little when I think back to former times.

Naturally I am resolving to do better this year, but that depends on the weather gods. This will be the year I finish Zola's Rougon Macquart opus though. At the other end of the reading scale, I may even convince myself to abandon books that aren't working.

My other aim is to get my books in translation back up to at least 50% of my reading

Books read in 2019 that didn't get discussed in my thread:

Fiction:

A Death in the Family by James Agee

The Sea by John Banville

Outside Looking In by T C Boyle

Death Comes to the Archbishop by Willa Cather (read on the property where it was written)

The Boat Rocker by Ha Jin

The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett

Gods and Beasts by Denise Mina

The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy

One Night in Winter by Simon Sebag-Montefiore

Autumn by Ali Smith

Emmeline by Charlotte Smith

A Game of Hide and Seek by Elizabeth Taylor

Lucia, Lucia by Adriana Trigiani

Fiction in Translation:

Beowulf translation by Seamus Heaney - superb, especially in the illustrated edition

By Night in Chile by Roberto Bolano Chile

The Night before Christmas by Nicholai Gogol Russia

Travelling Light by Tove Jansson Finland

Babi Yar by Anatoly Kuznetsov Ukraine

People in the Room by Norah Lange Argentina

Empty Words by Mario Levrero Uruguay

Light by Torgny Lindgren Norway

Nada by Jean Patrick Manchette France

To Leave with the Reindeer by Olivia Rosenthal France

Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb Hungary

Castle Gripsholm by Kurt Tucholsky Germany

Non- Fiction in Translation:

Memoirs from beyond the Grave by Chateaubriand France

Non-Fiction:

In Search of Lost Roses by Thomas Christopher

I Feel Bad about My Neck by Nora Ephron

My Garden (Book) by Jamaica Kincaid

Beatrix Potter's Gardening Life by Marta McDowell

Bringing a Garden to Life by Carol Williams

Book Club:

The Very Marrow of our Bones by Christine Higdon

Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver

Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death and Hard Truths in a Northern City by Tanya Talaga

Naturally I am resolving to do better this year, but that depends on the weather gods. This will be the year I finish Zola's Rougon Macquart opus though. At the other end of the reading scale, I may even convince myself to abandon books that aren't working.

My other aim is to get my books in translation back up to at least 50% of my reading

Books read in 2019 that didn't get discussed in my thread:

Fiction:

A Death in the Family by James Agee

The Sea by John Banville

Outside Looking In by T C Boyle

Death Comes to the Archbishop by Willa Cather (read on the property where it was written)

The Boat Rocker by Ha Jin

The Country of the Pointed Firs by Sarah Orne Jewett

Gods and Beasts by Denise Mina

The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy

One Night in Winter by Simon Sebag-Montefiore

Autumn by Ali Smith

Emmeline by Charlotte Smith

A Game of Hide and Seek by Elizabeth Taylor

Lucia, Lucia by Adriana Trigiani

Fiction in Translation:

Beowulf translation by Seamus Heaney - superb, especially in the illustrated edition

By Night in Chile by Roberto Bolano Chile

The Night before Christmas by Nicholai Gogol Russia

Travelling Light by Tove Jansson Finland

Babi Yar by Anatoly Kuznetsov Ukraine

People in the Room by Norah Lange Argentina

Empty Words by Mario Levrero Uruguay

Light by Torgny Lindgren Norway

Nada by Jean Patrick Manchette France

To Leave with the Reindeer by Olivia Rosenthal France

Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb Hungary

Castle Gripsholm by Kurt Tucholsky Germany

Non- Fiction in Translation:

Memoirs from beyond the Grave by Chateaubriand France

Non-Fiction:

In Search of Lost Roses by Thomas Christopher

I Feel Bad about My Neck by Nora Ephron

My Garden (Book) by Jamaica Kincaid

Beatrix Potter's Gardening Life by Marta McDowell

Bringing a Garden to Life by Carol Williams

Book Club:

The Very Marrow of our Bones by Christine Higdon

Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver

Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death and Hard Truths in a Northern City by Tanya Talaga

4AlisonY

Loving this year's Pantone colour! Much more palatable than others have been.

Look forward to following your reading in 2020.

Look forward to following your reading in 2020.

5avaland

>1 SassyLassy: While I was tempted to agree with you about 'classic blue' being a bit of a boring choice, but then saw the blueberries and the lapis lazuli and was smitten.

6ELiz_M

As soon as I saw the color in >1 SassyLassy: I let out a sigh of satisfaction. Such a soothing, calming color feels very necessary this year.

10SassyLassy

>4 AlisonY: >5 avaland: >6 ELiz_M: >7 NanaCC: >8 baswood: >9 lisapeet: It looks like Pantone really hit it on the mark with blue. It's a good thing I don't do colour selections!

>5 avaland: However, I definitely agree with you about the blueberries and lapis lazuli.

>9 lisapeet: Hadn't thought of blue from that perspective, but you're correct. Maybe there's a subliminal message there?

>5 avaland: However, I definitely agree with you about the blueberries and lapis lazuli.

>9 lisapeet: Hadn't thought of blue from that perspective, but you're correct. Maybe there's a subliminal message there?

11dchaikin

>2 SassyLassy: the last picture intrigues me. Looks like a rock under a microscope.

>3 SassyLassy: can I request a morsel on the Willa Cather? Did you like it? Did the context bother you at all, or even spoil it for you?

>9 lisapeet: 🙂 🌊 2020? We can dream for now, but I appreciate your perspective.

>3 SassyLassy: can I request a morsel on the Willa Cather? Did you like it? Did the context bother you at all, or even spoil it for you?

>9 lisapeet: 🙂 🌊 2020? We can dream for now, but I appreciate your perspective.

13SassyLassy

>9 lisapeet: >10 SassyLassy: Should have added that blue in Canada is the colour of the Conservative Party and red is for the Liberal Party, so sort of the reverse of US politics, although both these parties are to the left of the Democrats.

>11 dchaikin: I went back to the Economic Times article but it didn't bother to specify the exact rock.

About Death Comes for the Archbishop: I read this on Grand Manan Island, the place Willa Cather lived every summer from 1922 -1939. The cottage was on the actual property where Cather had lived, and I suppose this influenced my reading of the novel. All the cottages had books from that era, and in the short week there, I read 10% of my yearly total - it's amazing what a week without any form of electronics can do!

Anyway, that's not what you asked. The title of the book had intrigued me since I was a child, so when I found a copy in the cottage, it was the time to read it. I just reread your review of it, and found the remarks on the subtext perhaps stronger than mine. I did like the novel, particularly the friendship between the two priests in a strange land so far from home, as it developed into maturity over time and was maintained later over distance. I didn't find as much of the idea of religious superiority on the side of the missionaries as you did, although that sense is certainly implicit in any kind of missionary work. I was looking for it, but again, for the time the novel was written, I didn't really find it. There was certainly the juxtaposition in behaviours between the resident priest and the two newcomers, but it was a recognition at least of the evils that can arise from missionary and other forms of colonization. Unfortunately, I don't know the subsequent history of the Catholic church in New Mexico, but given what we know now, suspect it was no different from that in other areas.

I also liked Cather's treatment of the indigenous and Mexican peoples, which I felt also stood out for its time. The Spanish influence and history in the US is a part of its history which I find really interesting, and in this country at least is not something you really learn about in school.

I've read three other books by Cather, and liked The Professor's House best. I did have a strong negative reaction to Shadows on the Rock, which I felt was simplistic and presented Québec culture in a caricatured way. Perhaps this is an insight for me into the way you felt about the Archbishop, as you would have more knowledge of New Mexico history than I, and I felt Cather really lacked any depth when it came to New France.

While I was on Grand Manan, one of the other books I read was The Country of the Pointed Firs, and I felt this was the perfect place to read it.

>12 kidzdoc: And to you!

>11 dchaikin: I went back to the Economic Times article but it didn't bother to specify the exact rock.

About Death Comes for the Archbishop: I read this on Grand Manan Island, the place Willa Cather lived every summer from 1922 -1939. The cottage was on the actual property where Cather had lived, and I suppose this influenced my reading of the novel. All the cottages had books from that era, and in the short week there, I read 10% of my yearly total - it's amazing what a week without any form of electronics can do!

Anyway, that's not what you asked. The title of the book had intrigued me since I was a child, so when I found a copy in the cottage, it was the time to read it. I just reread your review of it, and found the remarks on the subtext perhaps stronger than mine. I did like the novel, particularly the friendship between the two priests in a strange land so far from home, as it developed into maturity over time and was maintained later over distance. I didn't find as much of the idea of religious superiority on the side of the missionaries as you did, although that sense is certainly implicit in any kind of missionary work. I was looking for it, but again, for the time the novel was written, I didn't really find it. There was certainly the juxtaposition in behaviours between the resident priest and the two newcomers, but it was a recognition at least of the evils that can arise from missionary and other forms of colonization. Unfortunately, I don't know the subsequent history of the Catholic church in New Mexico, but given what we know now, suspect it was no different from that in other areas.

I also liked Cather's treatment of the indigenous and Mexican peoples, which I felt also stood out for its time. The Spanish influence and history in the US is a part of its history which I find really interesting, and in this country at least is not something you really learn about in school.

I've read three other books by Cather, and liked The Professor's House best. I did have a strong negative reaction to Shadows on the Rock, which I felt was simplistic and presented Québec culture in a caricatured way. Perhaps this is an insight for me into the way you felt about the Archbishop, as you would have more knowledge of New Mexico history than I, and I felt Cather really lacked any depth when it came to New France.

While I was on Grand Manan, one of the other books I read was The Country of the Pointed Firs, and I felt this was the perfect place to read it.

>12 kidzdoc: And to you!

14dchaikin

Ok, wow... on your location and what a week. Lots to respond to here. I hope my comments on DCftA in my review made it clear she did win me over. I’m now planning to read all her books and that was the initial spark. She just left me lingering with some worry and uncertainty for the length of the book. The Professor’s House is the next book in my Litsy Cather group, I’ll start next week. More excited now. I was worried. Interesting about Shadows on the Rock.

I also hunted down the Economic Times article to try to figure out what that picture was of, and also came up empty...

I also hunted down the Economic Times article to try to figure out what that picture was of, and also came up empty...

15arubabookwoman

I hope to finish Rougon Macquart this year too. I started before rebeccanyc, but I haven't read any in probably 5 years or more. I'm on The Masterpiece.

Can I ask about Light by Torgny Lindgren? I have it on my TBR shelf, with no recollection of when or why I bought it, or what it's about. Did you like it?

Can I ask about Light by Torgny Lindgren? I have it on my TBR shelf, with no recollection of when or why I bought it, or what it's about. Did you like it?

16SassyLassy

>15 arubabookwoman: Light was an odd book, slow to get into. However, it grew on me and I did like it, getting to the point where I just kept reading. It is a sort of timeless fable, written in a way that you could imagine hearing it told to you. Perhaps that is a result of the setting and people involved (rural Sweden in an indeterminate past time).

It would be an excellent book for a day when you want to read but want something outside the ordinary.

What got you back reading Zola again?

>14 dchaikin: Coincidentally I read The Professor's House and Stoner fairly close together, and it was a good pairing.

I'll be following along with your Cather reading.

It would be an excellent book for a day when you want to read but want something outside the ordinary.

What got you back reading Zola again?

>14 dchaikin: Coincidentally I read The Professor's House and Stoner fairly close together, and it was a good pairing.

I'll be following along with your Cather reading.

17arubabookwoman

Light sounds intriguing and like something I’m going to like a lot.

Re Zola, the question really is why did I stop reading him. I really liked everything I’ve read by him. Then for some reason I just couldn’t get into The Masterpiece, surprising because I was really looking forward to Zola’s take on art. I set it aside and tried several times to start up again, and then one day I set it down, several years passed, and here we are. I’m hoping to read one Zola every other month or so.

Re Zola, the question really is why did I stop reading him. I really liked everything I’ve read by him. Then for some reason I just couldn’t get into The Masterpiece, surprising because I was really looking forward to Zola’s take on art. I set it aside and tried several times to start up again, and then one day I set it down, several years passed, and here we are. I’m hoping to read one Zola every other month or so.

18auntmarge64

I'm another who will enjoy following your Cather reading. I've read quite a few of hers and just love them.

19thorold

>17 arubabookwoman: I read The masterpiece recently, in my trip through Zola, and enjoyed it, although it’s a bit of an odd leap after Germinal (the more so since the protagonists of the two are brothers who seem unaware of each other’s existence...). It’s worth persevering with.

Let’s see if all three of us can get to Doctor Pascal this year!

Let’s see if all three of us can get to Doctor Pascal this year!

21arubabookwoman

>19 thorold: I do plan to persevere—hope those aren’t famous last words. Of the remaining volumes, I have previously read Earth, and I remember liking it almost as much as Germinal, so I’m looking forward to a reread.

22SassyLassy

>19 thorold: >21 arubabookwoman: A good resolution. It seems though that Doctor Pascal does not have a more current translation into English than 1957, so that may be tricky for some of us. I may have to put my ongoing French lessons into practice and see how long it takes me to get through! Otherwise I have been using mostly the more up to date Oxford translations.

>20 rocketjk: Happy reading to you too, wherever in the world it takes you.

>20 rocketjk: Happy reading to you too, wherever in the world it takes you.

23SassyLassy

Trying to adhere to my habit of a quick first read at the beginning of the year, I picked up this book at the library. Usually that first read is a mystery, but the boundaries of that definition seem to be shifting, so this year and last year the books didn't quite fit the bill, although they may have been described as such.

1. Cloud by Eric McCormack

first published 2014

finished reading January 7th, 2020

Cloud was a book that seemed to hold a lot of promise; a modern day gothic tale told by a man whose writing was compared on the back cover to Borges and Saki. Having read these latter two authors, as well as a previous book by McCormack, I knew this was overblown, but I had liked the previous book, so had hope.

The novel starts with a sort of prologue, involving the discovery of a nineteenth century book found in a second hand book store in Mexico. The book, The Obsidian Cloud was a collection of legends from an isolated Scottish mining town, Duncairn. Having spent a summer in the mining town in his youth, and had his heart broken there by the girl he considered his one true love, our protagonist bought the book and decided to send it off to a cultural centre in Glasgow to determine if there was any significance to the book.

Harry Steen then recounts his life and what brought him to Duncairn and Mexico, and so many more places in between. He also tells the developing story of the research into the old book. All starts off well enough, with descriptions of his early life in the slums of Glasgow in the 1930s and early WWII. As soon as Harry left home, however, and started to make his way in the world, things started to fall apart.

The mining town was in the moors. Cue Wuthering Heights. The love of his life lived in an isolated old stone home with her opium addicted father, who had come there to indulge his addiction in peace. McCormack often uses intertextuality in his writing, and sure enough, echoes of other books appear as our hero travels the world, everything from Lord Jim to The Island of Doctor Moreau.

His heart broken, Harry strikes out in the world, how else but by signing on as a deck hand on a freighter. In truth though, our hero is not a hero at all, but merely a sorry specimen who succeeds in spite of himself, mainly because he is spineless enough, and possibly lucky enough, to take direction from a dominant prospective employer, who sees in Harry a means to his own ends.

His travels now over, Harry moves to Canada to fulfill his destiny. All attempts at tension in the plot dissipated for me at this stage, as anyone familiar with a thinly disguised Kitchener - Waterloo would suffer a certain cognitive dissonance between the fictional menace of evil, and the environment of these two cities. Had Harry returned to Glasgow, the setting would have been much more conducive to such a plot.

All in all, an odd book. There is humour here, well-employed, for McCormack likes making use of the absurd. However, the promise of better that so often seemed to lie beneath the surface, never really materialized, and there was disappointment once again. As for the ending, the coincidence is just too unbelievable unless McCormack is trying to send up Dickens.

Having said all that, Cloud was published twelve years after McCormack's previous novel and after a period of life changes, so I will read another book by McCormack, hoping this one was just an aberration in his long writing career.

1. Cloud by Eric McCormack

first published 2014

finished reading January 7th, 2020

Cloud was a book that seemed to hold a lot of promise; a modern day gothic tale told by a man whose writing was compared on the back cover to Borges and Saki. Having read these latter two authors, as well as a previous book by McCormack, I knew this was overblown, but I had liked the previous book, so had hope.

The novel starts with a sort of prologue, involving the discovery of a nineteenth century book found in a second hand book store in Mexico. The book, The Obsidian Cloud was a collection of legends from an isolated Scottish mining town, Duncairn. Having spent a summer in the mining town in his youth, and had his heart broken there by the girl he considered his one true love, our protagonist bought the book and decided to send it off to a cultural centre in Glasgow to determine if there was any significance to the book.

Harry Steen then recounts his life and what brought him to Duncairn and Mexico, and so many more places in between. He also tells the developing story of the research into the old book. All starts off well enough, with descriptions of his early life in the slums of Glasgow in the 1930s and early WWII. As soon as Harry left home, however, and started to make his way in the world, things started to fall apart.

The mining town was in the moors. Cue Wuthering Heights. The love of his life lived in an isolated old stone home with her opium addicted father, who had come there to indulge his addiction in peace. McCormack often uses intertextuality in his writing, and sure enough, echoes of other books appear as our hero travels the world, everything from Lord Jim to The Island of Doctor Moreau.

His heart broken, Harry strikes out in the world, how else but by signing on as a deck hand on a freighter. In truth though, our hero is not a hero at all, but merely a sorry specimen who succeeds in spite of himself, mainly because he is spineless enough, and possibly lucky enough, to take direction from a dominant prospective employer, who sees in Harry a means to his own ends.

His travels now over, Harry moves to Canada to fulfill his destiny. All attempts at tension in the plot dissipated for me at this stage, as anyone familiar with a thinly disguised Kitchener - Waterloo would suffer a certain cognitive dissonance between the fictional menace of evil, and the environment of these two cities. Had Harry returned to Glasgow, the setting would have been much more conducive to such a plot.

All in all, an odd book. There is humour here, well-employed, for McCormack likes making use of the absurd. However, the promise of better that so often seemed to lie beneath the surface, never really materialized, and there was disappointment once again. As for the ending, the coincidence is just too unbelievable unless McCormack is trying to send up Dickens.

Having said all that, Cloud was published twelve years after McCormack's previous novel and after a period of life changes, so I will read another book by McCormack, hoping this one was just an aberration in his long writing career.

24avaland

Oh, sorry, you were disappointed with the first read of the year. Let's hope it only gets better.

25dchaikin

Interesting, Sassy. 12 years seems like a long time for a book that maybe doesn’t work. Like Lois, hoping you have better reading down the road.

26SassyLassy

Blue is definitely not the colour for me, and it startles me every time I open this page.

There is, however, blue I do like - something that has been obsessing me for months/years and taking up far too much reading time:

photo from The Independent

"Leave a light on..." Michael Russell

There is, however, blue I do like - something that has been obsessing me for months/years and taking up far too much reading time:

photo from The Independent

"Leave a light on..." Michael Russell

27haydninvienna

>26 SassyLassy: Moving to Scotland right now. I had the disorienting experience of entering the EU as a citizen on Friday and leaving it as a foreigner on Saturday.

28SassyLassy

>25 dchaikin: McCormack says he had a lot of upheaval in his life in the intervening 12 years, and found it difficult to settle into a writing rhythm.

>24 avaland: It does seem to be getting better, although I am behind already in reviews.

>27 haydninvienna: Disorientation indeed. Welcome to the thread and I hope this isn't just a metaphorical move.

>24 avaland: It does seem to be getting better, although I am behind already in reviews.

>27 haydninvienna: Disorientation indeed. Welcome to the thread and I hope this isn't just a metaphorical move.

29SassyLassy

This was my book club's choice for January. Despite my feeling about this particular book, I will finish the quartet.

2. Winter by Ali Smith

first published 2017

finished reading January 9, 2020

Winter was my second Ali Smith novel in as many months. The first was Autumn, which I truly liked. I had not read Smith before that, and was struck in both books by her exuberance around language, and her obvious love of its many complexities.

These are employed to the full in Winter. Without them, this would have been a rather dreary tale of a disconnected family, gathered together without celebration for Christmas. What the point of the story was, however, left me somewhat baffled. I found the symbolism of the young woman as Lux somewhat heavy handed. I picked up on the references to Brexit, to dissolution and breakdown, both political and personal, but there didn't seem to be a path forward, either positive or negative. It just was.

Winter perhaps can best be enjoyed like one of those songs whose lyrics (read storyline) don't mean much, but whose music (read rhythm and words) stays with you. Not well put, so in the words of The New Yorker's James Wood,

Well said.

_____________________

Wood's review: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/29/the-power-of-the-literary-pun

2. Winter by Ali Smith

first published 2017

finished reading January 9, 2020

Winter was my second Ali Smith novel in as many months. The first was Autumn, which I truly liked. I had not read Smith before that, and was struck in both books by her exuberance around language, and her obvious love of its many complexities.

These are employed to the full in Winter. Without them, this would have been a rather dreary tale of a disconnected family, gathered together without celebration for Christmas. What the point of the story was, however, left me somewhat baffled. I found the symbolism of the young woman as Lux somewhat heavy handed. I picked up on the references to Brexit, to dissolution and breakdown, both political and personal, but there didn't seem to be a path forward, either positive or negative. It just was.

Winter perhaps can best be enjoyed like one of those songs whose lyrics (read storyline) don't mean much, but whose music (read rhythm and words) stays with you. Not well put, so in the words of The New Yorker's James Wood,

At times you have the suspicion that Smith needs her characters to play around with words like this because she doesn't know how to animate them as actual human beings, motivated by need rather than whimsy. January 29, 2018

Well said.

_____________________

Wood's review: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/29/the-power-of-the-literary-pun

30SassyLassy

Winter was a library book, so by the time I got around to writing about it, it was long gone, and I had lost any jottings I had made. Naturally I found them today. This one stands out, linking as it does that book and my post at >26 SassyLassy::

It isn't a good enough answer, that one group of people can be in charge of the destinies of another group of people and choose whether to exclude them or include them.Ali Smith in Winter, p 206

31baswood

>26 SassyLassy: Lovely Blue thread

32labfs39

I was wondering if you might share a high-level mini-review of Journey by Moonlight. I read it two years ago, inspired by rebeccanyc. What did you think of it?

34SassyLassy

>32 labfs39:

Well I had to stop and think about this - which reflects well on the book, thus precluding a glib answer. So, just a few thoughts:

First of all, I would definitely recommend Journey by Moonlight. While as you know, it is a book full of death and suicide (the latter a "national obsession" according to translator Len Rix), it escapes being dark, balanced as it is with the daily life of Mihály, Erzsi, and their world. There is a grounding there that prevents the novel from becoming some kind of gothic cognate.

Mihály is someone we all know: the eternal adolescent, clinging to a world he never wants to leave, a world where consequences can never be all that bad. Meanwhile, those who made up that world around him have moved on, each in their own way, knowing there is no way to alter the past. I thought Szerb wrote this all superbly without judgement, letting events unfold as they will. Mihály's world was still haphazard in the extreme, but that may be what would eventually save him.

This is a book I wish I had read for the first time when I was 17 or so. It would have made a very different impression then, but it would have been one of those books to return to every fifteen years or so. It's still that book, but the starting point is different.

------------------

About a month ago, I saw the film Don't Look Now. The Venetian setting and sense of dreamlike menace made me think of Mihály wandering the city, and I wondered if there were any film adaptations. I don't see any references to one.

Have you read any other of Szerb's works?

35SassyLassy

My nearest town, population around 2,000, has three independent bookstores. Not only that, one of them even brings in not only NYRB classics, but also Icelandic authors. I wandered down there just after New Year's and came up with this next book.

3. Hotel Silence by Auður Ava Olafsdóttir translated from the Icelandic by Brian FitzGibbon (2018)

first published as Ör in 2016

finished reading January 9, 2020

At first I thought I had stumbled upon an Icelandic version of A Man called Ove. Disappointment, and my new resolve to stop reading books that don't engage, threatened a quick end. Luckily, what appeared to be the path of least resistance won out, and I settled in. After all, a quick read on a stormy day didn't seem like such a bad thing.

It turned out that Auður Ava was carefully building her story, just as her protagonist Jónas Ebeneser was carefully trying to finish his. Leaving Iceland so that no one he knew would find his body after his planned suicide, he wound un in a far away war torn seaside town now experiencing a cease fire. The cab driver told him

So began a new life for Jónas in a new country starting its own new life. There is the discovery of new cultures on both sides, each so old but so different. Asked when the last war was in his country, Jónas replied "1238".

Each day he found a reason to delay his end. Slowly he began to find a way into this world. There are no guarantees here. Developers have moved in, paving over the past. People mourning their country and their past are forced to adapt to survive. Auður Ava is wise enough to make no promises for the future. As the ending shows, however, the past never leaves us, something borne out by the Icelandic title, which translates as Scars

3. Hotel Silence by Auður Ava Olafsdóttir translated from the Icelandic by Brian FitzGibbon (2018)

first published as Ör in 2016

finished reading January 9, 2020

At first I thought I had stumbled upon an Icelandic version of A Man called Ove. Disappointment, and my new resolve to stop reading books that don't engage, threatened a quick end. Luckily, what appeared to be the path of least resistance won out, and I settled in. After all, a quick read on a stormy day didn't seem like such a bad thing.

It turned out that Auður Ava was carefully building her story, just as her protagonist Jónas Ebeneser was carefully trying to finish his. Leaving Iceland so that no one he knew would find his body after his planned suicide, he wound un in a far away war torn seaside town now experiencing a cease fire. The cab driver told him

Once there were ancient Roman ruins here, now it's just ruins... It will take us fifty years to build up the country again. The refugees won't come back while things are still a mess... And we don't get tourists anymore. We are no longer on the news. We are forgotten. We no longer exist.The Hotel Silence was just the place.

So began a new life for Jónas in a new country starting its own new life. There is the discovery of new cultures on both sides, each so old but so different. Asked when the last war was in his country, Jónas replied "1238".

Each day he found a reason to delay his end. Slowly he began to find a way into this world. There are no guarantees here. Developers have moved in, paving over the past. People mourning their country and their past are forced to adapt to survive. Auður Ava is wise enough to make no promises for the future. As the ending shows, however, the past never leaves us, something borne out by the Icelandic title, which translates as Scars

36thorold

>35 SassyLassy: That sounds like one to look out for: I enjoyed Butterflies in November

>34 SassyLassy: I agree that Journey by moonlight is a book we should all have read when we were 17! What a shame Mr Rix didn’t come along a bit earlier... I’ve still got Szerb’s short stories on the TBR.

>34 SassyLassy: I agree that Journey by moonlight is a book we should all have read when we were 17! What a shame Mr Rix didn’t come along a bit earlier... I’ve still got Szerb’s short stories on the TBR.

37labfs39

>35 SassyLassy: I am so envious! Three independent bookstores. Sigh. I have lived on the Florida panhandle for the last 22 months (but who's counting), where there are no bookstores. I've felt like I've been living in Penelope Fitzgerald's novel, The Bookshop, where the people in the town don't want a bookstore. It's hard to imagine. Thankfully change is on the horizon, as I'm moving.

Hotel Silence sounds intriguing. Is the place where Jonas moves to named? I immediately thought of the Dalmatian coast.

>34 SassyLassy: As for Journey by Moonlight, I hadn't thought about the impression the book would have made on me at a younger age. Did you see it as a coming-of-age story? I reread my review of the book just now, and in it I mention parallels with The Divine Comedy. Dan and I were just talking about how one begins to see connections to one's reading everywhere, and he is currently seeing Dante in everything. Now I am too.

Hotel Silence sounds intriguing. Is the place where Jonas moves to named? I immediately thought of the Dalmatian coast.

>34 SassyLassy: As for Journey by Moonlight, I hadn't thought about the impression the book would have made on me at a younger age. Did you see it as a coming-of-age story? I reread my review of the book just now, and in it I mention parallels with The Divine Comedy. Dan and I were just talking about how one begins to see connections to one's reading everywhere, and he is currently seeing Dante in everything. Now I am too.

38labfs39

P.S. I have The Pendragon Legend on my TBR.

39AlisonY

>35 SassyLassy: you're very lucky to have so many bookshops near you. The village I live in has over 2,000 residents and it can barely keep a corner shop going.

40thorold

>38 labfs39: The Pendragon legend is great fun, and a quick read. Quite different from Journey by moonlight.

41avaland

>35 SassyLassy: Ooo, she's a new Icelandic author for me. I just brought home the newest Olaf Olafsson, although I'm not sure when I will get to it. At the time I went to Iceland in 2010, there were still so few Icelandic authors translated. I had hoped to find more at a bookstore there, but there was nothing I hadn't seen before. Since then of course, there has been a great uptick of tourism in Iceland and with that an uptick of translations.

Hmm. Three independent bookstores in a town of 2,000 (all selling just new books?). Me thinks they are not in it for the money.

Hmm. Three independent bookstores in a town of 2,000 (all selling just new books?). Me thinks they are not in it for the money.

42SassyLassy

>36 thorold: I will be looking out for others by her.

>37 labfs39: The place in Hotel Silence is never mentioned, although like you, I immediately thought of the Dalmatian coast. Others have suggested Lebanon, but that didn't quite ring true with some of the details.

I read your review of Journey by Moonlight, as well as reviews by others in LT (after I did my own) and saw your mention of The Divine Comedy. The ideas of levels of states of being would certainly ring true here. I will be reading more Szerb, so will look for The Pendragon Legend, especially as >40 thorold: says it is great fun.

>39 AlisonY: >41 avaland: One of the bookstores is entirely second hand with some ephemera. It often doesn't open until after 20:00h, much to the confusion of tourists. One is mostly new. My favourite, which advertises itself as "Arguably one of the three best bookstores in" town, is maybe a 65:35 ratio of used to new, and has a great selection of nautical books. Here is a picture of it from a couple of years ago, with the recently much discussed on LT author John Lanchaster in view:

This is a wall of the used book section.

>41 avaland: Two of the three bookstores seem to be doing well; not sure about the quirky one, which I think is a labour of love.

I had an funny experience just before Labour Day. I was standing in line to pay with five books in my hands. Two people up from me was an American at the cash. She was asking how the bookstore ever stayed in business in the winter, or did it close, because obviously in her tourist eyes, nobody in a place like this would ever read - only tourists like her would keep them in business! The person at the till was making eye contact with me, smiling, as she reassured the tourist that indeed they were able to operate year round, and that there were local readers.

I think one of the reasons the two stores with new books on offer are successful is that a lot of readers here are stubborn enough to order from them instead of online, even if it is slightly more expensive. Also, the one with nautical books is trying to promote that as a specialty; not a bad idea in this shipbuilding town. If you've ever been to Dogtown Books in Gloucester MA (one of my favourites), the local store's used books' inventory seems like a smaller version (although I haven't been there since it changed hands in 2018, and suspect I would miss Bob).

>37 labfs39: The place in Hotel Silence is never mentioned, although like you, I immediately thought of the Dalmatian coast. Others have suggested Lebanon, but that didn't quite ring true with some of the details.

I read your review of Journey by Moonlight, as well as reviews by others in LT (after I did my own) and saw your mention of The Divine Comedy. The ideas of levels of states of being would certainly ring true here. I will be reading more Szerb, so will look for The Pendragon Legend, especially as >40 thorold: says it is great fun.

>39 AlisonY: >41 avaland: One of the bookstores is entirely second hand with some ephemera. It often doesn't open until after 20:00h, much to the confusion of tourists. One is mostly new. My favourite, which advertises itself as "Arguably one of the three best bookstores in" town, is maybe a 65:35 ratio of used to new, and has a great selection of nautical books. Here is a picture of it from a couple of years ago, with the recently much discussed on LT author John Lanchaster in view:

This is a wall of the used book section.

>41 avaland: Two of the three bookstores seem to be doing well; not sure about the quirky one, which I think is a labour of love.

I had an funny experience just before Labour Day. I was standing in line to pay with five books in my hands. Two people up from me was an American at the cash. She was asking how the bookstore ever stayed in business in the winter, or did it close, because obviously in her tourist eyes, nobody in a place like this would ever read - only tourists like her would keep them in business! The person at the till was making eye contact with me, smiling, as she reassured the tourist that indeed they were able to operate year round, and that there were local readers.

I think one of the reasons the two stores with new books on offer are successful is that a lot of readers here are stubborn enough to order from them instead of online, even if it is slightly more expensive. Also, the one with nautical books is trying to promote that as a specialty; not a bad idea in this shipbuilding town. If you've ever been to Dogtown Books in Gloucester MA (one of my favourites), the local store's used books' inventory seems like a smaller version (although I haven't been there since it changed hands in 2018, and suspect I would miss Bob).

43avaland

>41 avaland: Bookstores are still a labor of love or a cause of some kind (perhaps both) and most owners are happy to end the year in the black, to be able to pay their bills and employees and maybe have a wee bit leftover. Jeff Bezos is laughing all the way to the bank, though.

I have not been to Dogtown Books, as I am rarely in the north-of-Boston 'burbs these days. We have four used bookstores north of us in and around a tiny college town about 45 minutes to an hour away. There is a nice restaurant there that overlooks the river and a "destination" quilt shop just down the street, so it's a nice outing once in a while.

I have not been to Dogtown Books, as I am rarely in the north-of-Boston 'burbs these days. We have four used bookstores north of us in and around a tiny college town about 45 minutes to an hour away. There is a nice restaurant there that overlooks the river and a "destination" quilt shop just down the street, so it's a nice outing once in a while.

44baswood

Yesterday I discovered le Cochon Bleu in Lectoure (South West France) which brilliantly combines two of my favourite pleasures in life eating(and drinking) and reading. We went there with some friends and while I was eating an excellent maigret de canard I was in touching distance of wonderful books. Heaven. We were invited and so our friends paid for the meal and I bought books for everyone.

46SassyLassy

>44 baswood: I'd take you out to lunch there any day! What a lovely looking bookstore. When are you going back?

I see colour is creeping into the spines on the books. Are those imports or is the industry changing?

I see colour is creeping into the spines on the books. Are those imports or is the industry changing?

47SassyLassy

This book was found in a tidyup. At first I had no idea where it had come from. Then I realized it belonged to a friend, so since I was going to the city to visit her, I read it before taking it back.

4. The Breakdown by B A Paris

first published 2017

finished reading January 18, 2020

What would you do if on a dark rainy night on a lonely wooded road you saw a car pulled over on the side, with a solitary driver at the wheel? Cass pulled over in front of the parked vehicle to help. After all, it was a quiet road known only to locals. However, unable to clearly see the driver through the rain streaked windows, she reconsidered, pulled back out and drove home.

Next day, it was announced that a murder victim had been discovered in that spot. Cass's first thought was guilt - she could have helped. Then guilt turned to fear. What if the murderer had seen her and would now come after her? Hadn't the time of her stop coincided with the time frame given by police? Turns out Cass even actually knew the victim, making her feel even worse.

This is just the beginning. The rest of the novel is devoted to the aftermath for Cass and finding the murderer, also told from her perspective. Paris has thrown in a few contemporary devices to pad out the process. At the time of the murder, Cass was on bereavement and stress leave following her mother's untimely death from complications arising from early onset dementia. Could Cass be suffering from the same disease? Is that why she feels so unfocussed and forgetful?

It's all a pretty thin peg on which to hang a plot. Part of the solution seemed apparent by page 17. Giving some credit to the author though, she did manage to portray Cass's fears and behaviour in a believable and sympathetic way.

Not a book I would recommend, but it worked as an escape on a stormy day. Turns out my friend felt the same way. It had been on her discard pile and was returned there.

4. The Breakdown by B A Paris

first published 2017

finished reading January 18, 2020

What would you do if on a dark rainy night on a lonely wooded road you saw a car pulled over on the side, with a solitary driver at the wheel? Cass pulled over in front of the parked vehicle to help. After all, it was a quiet road known only to locals. However, unable to clearly see the driver through the rain streaked windows, she reconsidered, pulled back out and drove home.

Next day, it was announced that a murder victim had been discovered in that spot. Cass's first thought was guilt - she could have helped. Then guilt turned to fear. What if the murderer had seen her and would now come after her? Hadn't the time of her stop coincided with the time frame given by police? Turns out Cass even actually knew the victim, making her feel even worse.

This is just the beginning. The rest of the novel is devoted to the aftermath for Cass and finding the murderer, also told from her perspective. Paris has thrown in a few contemporary devices to pad out the process. At the time of the murder, Cass was on bereavement and stress leave following her mother's untimely death from complications arising from early onset dementia. Could Cass be suffering from the same disease? Is that why she feels so unfocussed and forgetful?

It's all a pretty thin peg on which to hang a plot. Part of the solution seemed apparent by page 17. Giving some credit to the author though, she did manage to portray Cass's fears and behaviour in a believable and sympathetic way.

Not a book I would recommend, but it worked as an escape on a stormy day. Turns out my friend felt the same way. It had been on her discard pile and was returned there.

48SassyLassy

Another book from another friend - I just may have to get my own copy.

5. Life in the Garden by Penelope Lively

first published 2017

finished reading January 27, 2020

Penelope Lively is one of those authors I've always meant to read. It seemed odd, however, to start with Life in the Garden, as the author looked back over her eighty plus years, her life in both metaphorical literary gardens and in real gardens. Even if you don't garden yourself, if you think your life has nothing to do with such things, just think of all those gardens you've read of, from Peter Rabbit, through Alice in Wonderland to My Antonia and Zola's The Sin of Abbé Mouret. Gardens are at the heart of these books; they couldn't have been written without them.

When Lively said in her introduction, right there on page 1,

Lively jumped right in with Virginia Woolf:

Children who are read to and read are introduced to the garden early, as a place not only of magic and wonder, but also as a narrative of life through fable. Not only the books above, but others like The Secret Garden and Tom's Midnight Garden are singled out as examples over the generations. With books like these in mind, Lively quotes Auden writing on Alice in Wonderland:

Turning to actual gardens, Lively takes on the "fashionable garden" devoting a full chapter to it. As she says "By their gardens ye shall know them". Mansfield Park makes an appearance here, as once again a character is revealed through his comments on a garden. Moving from fashion to style as a social indicator, she delves into The Age of Innocence.

There's a lot more here for people who love gardens and/or gardening, including a bit on one of my favourite topics with which to bore my city friends: the difficulties of rural gardening versus urban gardening.

Lively of course was privileged to have grown up in lovely gardens, and to always have been lucky enough to be able to pursue her interest in her own succession of gardens. She herself acknowledges this. However, she is not about to let the idea of the garden disappear in an increasingly urbanized world. She cites a horrifying incident from her children's book writing years when "... politically correct children's book editors reminded authors sternly that a garden is not an appropriate feature in a children's book, on the grounds that most - or many - children don't have one, forgetting that we read to escape and expand our circumstances, not to replicate them."

At the end of this book, I was left wondering, as fewer and fewer people have an acquaintance with gardens, let alone the natural world, how will these books be read and interpreted in the future? Will their meaning be lost? What happens if Candide stops cultivating the garden in all its senses?

5. Life in the Garden by Penelope Lively

first published 2017

finished reading January 27, 2020

Penelope Lively is one of those authors I've always meant to read. It seemed odd, however, to start with Life in the Garden, as the author looked back over her eighty plus years, her life in both metaphorical literary gardens and in real gardens. Even if you don't garden yourself, if you think your life has nothing to do with such things, just think of all those gardens you've read of, from Peter Rabbit, through Alice in Wonderland to My Antonia and Zola's The Sin of Abbé Mouret. Gardens are at the heart of these books; they couldn't have been written without them.

When Lively said in her introduction, right there on page 1,

"I always pay attention when a writer conjures up a garden, when gardening becomes an element of fiction. I find myself wondering what is going on here. Is this garden deliberate or merely fortuitous? And it is nearly always deliberate, a garden contrived to serve a narrative process, to create atmosphere, to furnish a character.I perked right up, for this is exactly how I feel.

Lively jumped right in with Virginia Woolf:

'...in her fiction, gardens and plants are manipulated, reinvented, bent to the purpose of the narrative in question. This happens time and again... in different hands; the fictional garden will have roots in its creator's own experience, but on the page it becomes a metaphor.

Children who are read to and read are introduced to the garden early, as a place not only of magic and wonder, but also as a narrative of life through fable. Not only the books above, but others like The Secret Garden and Tom's Midnight Garden are singled out as examples over the generations. With books like these in mind, Lively quotes Auden writing on Alice in Wonderland:

There are good books which are only for adults, because their comprehension presupposes adult experiences, but there are no good books which are only for children.

Turning to actual gardens, Lively takes on the "fashionable garden" devoting a full chapter to it. As she says "By their gardens ye shall know them". Mansfield Park makes an appearance here, as once again a character is revealed through his comments on a garden. Moving from fashion to style as a social indicator, she delves into The Age of Innocence.

There's a lot more here for people who love gardens and/or gardening, including a bit on one of my favourite topics with which to bore my city friends: the difficulties of rural gardening versus urban gardening.

Lively of course was privileged to have grown up in lovely gardens, and to always have been lucky enough to be able to pursue her interest in her own succession of gardens. She herself acknowledges this. However, she is not about to let the idea of the garden disappear in an increasingly urbanized world. She cites a horrifying incident from her children's book writing years when "... politically correct children's book editors reminded authors sternly that a garden is not an appropriate feature in a children's book, on the grounds that most - or many - children don't have one, forgetting that we read to escape and expand our circumstances, not to replicate them."

At the end of this book, I was left wondering, as fewer and fewer people have an acquaintance with gardens, let alone the natural world, how will these books be read and interpreted in the future? Will their meaning be lost? What happens if Candide stops cultivating the garden in all its senses?

49baswood

>48 SassyLassy: It took Candide some time to discover his garden. Some people never get out of their gardens. Sound like you enjoyed the Penelope Lively book.

>46 SassyLassy: Most of the spines of French books are white or of one colour - I am thinking of sandstone (I don't know what the official colour for Gallimard is) the red flashes usually indicate a prize winner or a scholars edition.

However most science fiction and crime novels are multicoloured and so you can tell at a glance where they are kept. I am just starting to enjoy myself in French bookshops, but I have little knowledge of the publishing houses. I am sure some people on these threads know a lit more than I do.

The books I bought for myself were:

La Petite Bijou by Patrick Modiano

En attendant Bojangles by Olivier Bourdeaut

>46 SassyLassy: Most of the spines of French books are white or of one colour - I am thinking of sandstone (I don't know what the official colour for Gallimard is) the red flashes usually indicate a prize winner or a scholars edition.

However most science fiction and crime novels are multicoloured and so you can tell at a glance where they are kept. I am just starting to enjoy myself in French bookshops, but I have little knowledge of the publishing houses. I am sure some people on these threads know a lit more than I do.

The books I bought for myself were:

La Petite Bijou by Patrick Modiano

En attendant Bojangles by Olivier Bourdeaut

50edwinbcn

I am not surprised you would be interested in Penelope Lively, and I would be very interested myself to read Life in the Garden.

I don't know whether this essay is included in that book but otherwise you might like reading Lively's essay on Virginia Woolf and gardens "Penelope Lively on Virginia Woolf: Serious Gardener?

On the Rich Landscapes of To the Lighthouse and "Kew Gardens", the link to which I posted on the MESSAGE BOARD last week (message #21).

Just ten days ago, I finished reading her autobiographical book A House Unlocked, published in 2001, which also has three chapters on nature and gardening.

I don't know whether this essay is included in that book but otherwise you might like reading Lively's essay on Virginia Woolf and gardens "Penelope Lively on Virginia Woolf: Serious Gardener?

On the Rich Landscapes of To the Lighthouse and "Kew Gardens", the link to which I posted on the MESSAGE BOARD last week (message #21).

Just ten days ago, I finished reading her autobiographical book A House Unlocked, published in 2001, which also has three chapters on nature and gardening.

51dchaikin

>29 SassyLassy: Wood - phew. He kind of spoils the fun with that sharp comment. He’s spot on

>47 SassyLassy: so, of course with that opening I’m thinking Dante. Sorry...

>48 SassyLassy: wonderful review. You might have sold me on this book. I’m already rethinking The Professor’s House - since the professor cares quite passionately for a garden.

>47 SassyLassy: so, of course with that opening I’m thinking Dante. Sorry...

>48 SassyLassy: wonderful review. You might have sold me on this book. I’m already rethinking The Professor’s House - since the professor cares quite passionately for a garden.

52sallypursell

>48 SassyLassy: What makes you say that gardening is declining. That certainly isn't so in my neck of the woods. More people in my acquaintanceship are gardening than ever before. Some of them are nearly boring about their gardens. There are more books, more gardens, more time in the garden. I was dragged to a nursery by a friend yesterday, to buy some plants, some seeds, and some attractive pots. Two of my sons are deeply into it, my husband, and one daughter.

53markon

>48 SassyLassy: Life in the garden is definitely a book bullet. I'm hoping it will get a little warmer here tomorrow so I can get outside in my yard. Hoping I can at least get some herbs planted this year. It's been awhile since I've tried a garden.

55SassyLassy

>54 avaland: Thanks - see PM

56SassyLassy

Well it is a while since I posted. This next is out of order, but since I posted it for the Reading Globally South Africa quarter, I thought I would post it here too.

13.Praying Mantis by André Brink

first published 2005

finished reading April 16, 2020

Cupido Cockroach did not have a father. His mother had told him many stories about how he came to be. Cupido's favourite was of an eagle swooping down to pick him up from the veld where he had been left to die, only to be flown in the eagle's beak untold miles before being dropped in the lap of the sleeping woman who would become his mother.

This eagle was not the only animal to feature in Cupido's history. That very night, the child died, and was laid out to be buried the next morning. When the hung-over villagers arrived to bury him, they saw a bright green mantis praying over the body, restoring him to life. Clearly, this child was destined for a life that would take him far beyond this farm. As his mother said, "If you ask me, he has been chosen to become a man like no other... he will be a free man."

The year was 1760 and freedom was not a likely proposition for this child of a Hottentot labourer. Cupido's childhood and adolescence did not offer much hope of fulfillment for his mother's prophecy. While he was bright and ambitious, he was not at all diligent, preferring instead to pursue those things which interested him. When Cupido was about seventeen, an itinerant pedlar turned up on the farm. Like Cupido's now disappeared mother, Servaas Ziervogel was a teller of tales and a singer, but this man's tales came from something called the Gospel. There were other stories too, of lands far beyond the horizon, places with strange and unusual names like Damascus, Vladivostock and even Pluto. Cupido absorbed them all. It was a time of learning. Ziervogel taught him to read, but also gave him a taste for arrack, women, and fighting.

Eventually the two parted amicably. Cupido wooed and won the indomitable Anna Vigilant. Anna believed true freedom was only given to white people. A soap-maker, her desire to be free had led her to put her foot in the boiling lye in an effort to whiten herself, as her soap whitened everything else. She was left lame for life. She was also left with a strong distaste for the ways of the white people, especially when it came to their religion. Cupido, on the other hand, felt its pull and succumbed.

Brink has used a straightforward narrative up to this point. Part II, covering the years 1802-1815, switches format and perspective. It purports to be written retrospectively in memoir form by the disgraced Reverend James Read. It is set against a warring background between English and Dutch for control of South Africa. It depicts more immediately the struggle for domination of all around them, be it land, animals, or souls. Read is unusual in his sympathies for, and belief in, the indigenous peoples. He happily took on Cupido as a protégé. Learning in turn from Cupido, Read developed in his mind an almost mystical feeling for the land. Travelling with Cupido, he

While continuing with some of Cupido's more extreme eccentricities, this section introduces hard reality. Brink, through Read, does not hold back on the treatment of the indigenous peoples by the Europeans.

Read's summary ended with the year 1815. Part III returns to the narrative structure of Part I. Cupido was now far in the outback, in an area prone to drought. Quoting Deuteronomy, Brink says "He found him in a desert land, and in the waste howling wilderness." Like many before him, Cupido was being tested in the desert by his faith. The question for him was which faith: the animist ones of the people, or the new ones brought by the Europeans.

Although Praying Mantis deals with questions of belief, it is not a book with an obtrusive religious message. Rather, it takes the reader back to a time when two groups of peoples came together with very different ideas of the world. How were new ideas to be reconciled with existing ones, or was reconciliation even possible?; would cultural clashes and their resulting wars ever be resolved?

In a note at the end of the novel, Brink suggests he may have had difficulty writing it. He started it in 1984, stopped, started again in 1992. However, it was not until 2004 that he actually finished it, after resolving to write a book for his 70th birthday. What precipitated the fits and starts he doesn't say. He does say though that Cupido Cockroach was a real person, Cupido Kakkerlak, whose story appears from time to time in records of the London Missionary Society in South Africa, and also in academic journals. Reverend Read and many others of the characters are also based on real people. Knowing this made Cupido's faults and struggles, his drive and determination, credible in a way they might not otherwise have been. As Brink says "... the enigma of another's life can only be grasped through the imagination (which is no less reliable than memory)."

13.Praying Mantis by André Brink

first published 2005

finished reading April 16, 2020

Cupido Cockroach did not have a father. His mother had told him many stories about how he came to be. Cupido's favourite was of an eagle swooping down to pick him up from the veld where he had been left to die, only to be flown in the eagle's beak untold miles before being dropped in the lap of the sleeping woman who would become his mother.

This eagle was not the only animal to feature in Cupido's history. That very night, the child died, and was laid out to be buried the next morning. When the hung-over villagers arrived to bury him, they saw a bright green mantis praying over the body, restoring him to life. Clearly, this child was destined for a life that would take him far beyond this farm. As his mother said, "If you ask me, he has been chosen to become a man like no other... he will be a free man."

The year was 1760 and freedom was not a likely proposition for this child of a Hottentot labourer. Cupido's childhood and adolescence did not offer much hope of fulfillment for his mother's prophecy. While he was bright and ambitious, he was not at all diligent, preferring instead to pursue those things which interested him. When Cupido was about seventeen, an itinerant pedlar turned up on the farm. Like Cupido's now disappeared mother, Servaas Ziervogel was a teller of tales and a singer, but this man's tales came from something called the Gospel. There were other stories too, of lands far beyond the horizon, places with strange and unusual names like Damascus, Vladivostock and even Pluto. Cupido absorbed them all. It was a time of learning. Ziervogel taught him to read, but also gave him a taste for arrack, women, and fighting.

Eventually the two parted amicably. Cupido wooed and won the indomitable Anna Vigilant. Anna believed true freedom was only given to white people. A soap-maker, her desire to be free had led her to put her foot in the boiling lye in an effort to whiten herself, as her soap whitened everything else. She was left lame for life. She was also left with a strong distaste for the ways of the white people, especially when it came to their religion. Cupido, on the other hand, felt its pull and succumbed.

Brink has used a straightforward narrative up to this point. Part II, covering the years 1802-1815, switches format and perspective. It purports to be written retrospectively in memoir form by the disgraced Reverend James Read. It is set against a warring background between English and Dutch for control of South Africa. It depicts more immediately the struggle for domination of all around them, be it land, animals, or souls. Read is unusual in his sympathies for, and belief in, the indigenous peoples. He happily took on Cupido as a protégé. Learning in turn from Cupido, Read developed in his mind an almost mystical feeling for the land. Travelling with Cupido, he

came to see it through our brother's eyes and be made aware of the manifold minutiae in which life can express itself: an ever renewed discovery of riches in indigenous peoples, animals, birds, insects, plants, even rocks and stones.

While continuing with some of Cupido's more extreme eccentricities, this section introduces hard reality. Brink, through Read, does not hold back on the treatment of the indigenous peoples by the Europeans.

Read's summary ended with the year 1815. Part III returns to the narrative structure of Part I. Cupido was now far in the outback, in an area prone to drought. Quoting Deuteronomy, Brink says "He found him in a desert land, and in the waste howling wilderness." Like many before him, Cupido was being tested in the desert by his faith. The question for him was which faith: the animist ones of the people, or the new ones brought by the Europeans.

Although Praying Mantis deals with questions of belief, it is not a book with an obtrusive religious message. Rather, it takes the reader back to a time when two groups of peoples came together with very different ideas of the world. How were new ideas to be reconciled with existing ones, or was reconciliation even possible?; would cultural clashes and their resulting wars ever be resolved?

In a note at the end of the novel, Brink suggests he may have had difficulty writing it. He started it in 1984, stopped, started again in 1992. However, it was not until 2004 that he actually finished it, after resolving to write a book for his 70th birthday. What precipitated the fits and starts he doesn't say. He does say though that Cupido Cockroach was a real person, Cupido Kakkerlak, whose story appears from time to time in records of the London Missionary Society in South Africa, and also in academic journals. Reverend Read and many others of the characters are also based on real people. Knowing this made Cupido's faults and struggles, his drive and determination, credible in a way they might not otherwise have been. As Brink says "... the enigma of another's life can only be grasped through the imagination (which is no less reliable than memory)."

57kidzdoc

Great review of Praying Mantis, Sassy! It sounds very intreresting, so I'll add it to my wish iist.

58baswood

Enjoyed your review of Praying Mantis

59avaland

>56 SassyLassy: How interesting. And it reminds me I have one or two of Brink's work unread on the shelf (from back when I was heavily reading African lit).

60SassyLassy

>57 kidzdoc: >58 baswood: >59 avaland: Thanks all. It was quite a change from the other Brink I've read: The Wall of the Plague, so it wasn't what I was expecting. It worked out well though.

61dchaikin

It’s a terrific review, and interesting that it was on real characters. South Africa has such a fascinating history.

62SassyLassy

Although read in February, early in the year, this may well be one of my favourite books of the year. Living a two day sail away from Cape Cod, in a place very similar to that described by Beston, one where the shoreline can be a daily walk, his descriptions really spoke to me, and so I have quoted him perhaps more that I should, as his writing gives such a marvellous sense of this stretch of ocean.

6. The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod by Henry Beston

first published 1928

finished reading February 6, 2020

One hundred years ago Cape Cod was a very different place than the busy area it is today. In 1924, when Henry Beston first saw the ocean side of the peninsula wrapping Cape Cod Bay, it was a wild and uninhabited place. As Beston described it For twenty miles this last and outer earth faces the ever hostile ocean in the form of a great eroded cliff of earth and clay, the undulations and levels of whose rim now stand a hundred, now a hundred and fifty feet above the tides. Worn by the breakers and the waves, it still stands bold."

The immediate attraction and pull of the shoreline was such that the next year he bought fifty acres of dunes, and built himself the Fo'castle, a 20' x 16' two room cottage. There was no road in, only a trail. The closest neighbours were the coast guards at the Nauset station two miles away. In September 1926, Beston went to his cottage for a couple of weeks. Somehow, without any real plan, the two weeks lengthened into a year. As Beston put it,

So began a remarkable immersion year in the natural world. Beston's observations and writing are such that the reader hears the sea, smells the salt, feels the wind the sun and the rain. Bird populations change with the season, so prevalent in spring and fall, almost absent in winter apart from the eternal gulls. Beaton is able to put all these natural phenomena into words. Speaking of the ocean, he said

Beston's writing is still as fresh today as when his book was first published in 1928. This edition was a 75th anniversary publication. As for the Fo'castle, Beston donated it to the Massachusetts Audubon Society in 1960. It was swept out to sea in February 1978 in a huge storm. Beston's dunes survive, however, in the Cape Cod National Seashore, the creation of which was partly inspired by his writing.

6. The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod by Henry Beston

first published 1928

finished reading February 6, 2020

One hundred years ago Cape Cod was a very different place than the busy area it is today. In 1924, when Henry Beston first saw the ocean side of the peninsula wrapping Cape Cod Bay, it was a wild and uninhabited place. As Beston described it For twenty miles this last and outer earth faces the ever hostile ocean in the form of a great eroded cliff of earth and clay, the undulations and levels of whose rim now stand a hundred, now a hundred and fifty feet above the tides. Worn by the breakers and the waves, it still stands bold."

The immediate attraction and pull of the shoreline was such that the next year he bought fifty acres of dunes, and built himself the Fo'castle, a 20' x 16' two room cottage. There was no road in, only a trail. The closest neighbours were the coast guards at the Nauset station two miles away. In September 1926, Beston went to his cottage for a couple of weeks. Somehow, without any real plan, the two weeks lengthened into a year. As Beston put it,

... as the year lengthened into autumn, the beauty and mystery of this earth and outer sea so possessed and held me that I could not go ... The flux and reflux of ocean, the incomings of waves, the gatherings of birds, the pilgrimages of the peoples of the sea, winter and storm, the splendour of autumn and the holiness of the spring - all these were part of the great beach. The longer I stayed the more eager I was to know this coast and to share its mysterious and elemental life.

So began a remarkable immersion year in the natural world. Beston's observations and writing are such that the reader hears the sea, smells the salt, feels the wind the sun and the rain. Bird populations change with the season, so prevalent in spring and fall, almost absent in winter apart from the eternal gulls. Beaton is able to put all these natural phenomena into words. Speaking of the ocean, he said

The sea has many voices. Listen to the surf, really lend it your ears, and you will hear in it a world of sounds: hollow boomings and heavy roarings, great watery tumblings and tramplings, long hissing seethes, sharp, rifle-shot reports, splashes, whispers, the grinding undertone of stones, and sometimes vocal sounds that might be the voices of people in the sea. And not only is the great sound varied in the manner of its making, it is also constantly changing its tempo, its pitch, its accent and its rhythm, being now loud and thundering, now almost placid, now furious, now grave and solemn-slow, now a simple measure, now a rhythm monstrous and with a sense of elemental will.This will is dangerous at times. Fishing schooners wash ashore. That winter even a Coast Guard vessel was destroyed. Wreckage from previous disasters lies entombed in the constantly shifting sand. "Eighteenth century pirates, stately British merchantmen of the mid-Victorian years, whaling brigs, Salem East India traders, Gloucester fishermen, and a whole host of forgotten Nineteenth Century schooners -- all these have strewn this beach with broken spars and dead. Although this book covers only the one year, there is a remarkable sense of the eternal cycle of the seasons, of the paradox of repeating patterns coupled with constant change. There is a reassurance in these rituals, something that those who live by the ocean recognize, if only subconsciously, something that keeps bringing them back.

Beston's writing is still as fresh today as when his book was first published in 1928. This edition was a 75th anniversary publication. As for the Fo'castle, Beston donated it to the Massachusetts Audubon Society in 1960. It was swept out to sea in February 1978 in a huge storm. Beston's dunes survive, however, in the Cape Cod National Seashore, the creation of which was partly inspired by his writing.

63SassyLassy

the Fo'castle

image from Harvard Magazine

the end of the Fo'Castle

image from Digital Commonwealth

66tonikat

>62 SassyLassy: loved that, I'm at our bit of sea most days now and will listen afresh - in feb we had strange calm, calmer than I've ever known, v. spooky (at night under a full moon in a haven I've heard witches associated with (as a kid))-- but it soon got back to normal. We have big beaches too, I'm guessing not as big.

67SassyLassy

A big leap ahead from book number 6 to 21. I wanted to get it in during the Reading Globally's second quarter.

21. In a Strange Room: Three Journeys by Damon Galgut

first published 2010

finished reading June 12, 2020

Two men, travelling in opposite directions, met each other on the road between Mycenae and Sparta. They chatted a few minutes as walkers on an empty trail do, and then each continued on his way. That night, the unnamed South African found the German, Reiner, in his room at the hostel. They spent two days together before continuing on their separate journeys.

They wrote each other for the next two years, and then decided to embark on a walking trip together. Lesotho was the country chosen. In this first of the three recorded journeys, the narrator, whom we come to know as Damon, is young, unsure of himself. For this journey, he calls himself 'The Follower'. As they walked, Reiner took more and more control of the trip, slowly and oh so assuredly. Damon, furious, repressed his growing rage. Can there be conflict if one side refuses to engage? "... in the end you are always more tormented by what you didn't do than what you did, actions already performed can always be rationalized in time, the neglected deed might have changed the world.".

A few years went by and a more mature, more assured Damon was now travelling in Zimbabwe, but still just as lonely. This trip was more promising, but there was a restlessness, a constant need to move on. Zambia, Malawi, small groups of travellers forming and reforming. "It's all touching and happy, but he's the odd one out here, he keeps a distance between himself and them, no matter how friendly they are." He is, after all, South African, and they all know how messed up that is.